Foster Parent Handbook

Introduction

Colour Code Key:

Fosterplus Policies, Procedures and Guidance

Legislation and Government Guidance

General Sources and Good Practice Information

Office Addresses

Fosterplus (Fostercare) Ltd herein after referred to as Fosterplus is an independent fostering agency. We were established in 1996, and opened our first office in Scotland in 2000, as a service for children and young people, based on the principles of high quality foster care and effective support systems, with the needs of every child central to what we do. Since that time, we have grown and developed across England and Scotland and we are currently part of a group of high quality fostering services managed by Polaris Community.

Fosterplus is organised into a number of local fostering teams with office bases across the central belt of Scotland.

Fosterplus (Fostercare) Ltd Offices

Ayr

1 Racecourse Road, Ayr, KA7 2UP

Tel: 01292 288990

Edinburgh

Tel: 0131 241 6200

Glasgow

The Arc, Unit 7, 25 Colquhoun Avenue, Hillington Park, Glasgow, G52 4BN

Tel: 0141 457 7127

Fosterplus believes that all children and young people needing substitute care should have the opportunity to live in a family home. We have a Statement of Purpose that describes the aims and objectives of the fostering services we provide. A copy of this is available in the charms downloads area.

Purpose of the Foster Parent Handbook

This foster care handbook is intended to be both a source of information and a good practice guide for foster parents. It should be of value also to Fosterplus supervising social workers who supervise and support foster parents, and for all staff involved with and connected to Fosterplus. The handbook cannot cover every situation that foster parents will encounter and it is not a substitute for a good working relationship between foster parents, supervising social workers, other staff and volunteers, and the parents and social worker for the child.

Each child or young person is an individual with a unique personality and can expect a response from all those who are caring for them that is tailored to their needs, but the foster care handbook is a guide for many aspects of day-to-day practice. It also covers the legal and social work framework and clarifies the policies and, at times, the rules that apply to foster care. It is therefore a useful reference tool for foster parents as well as supervising social workers.

There are separate handbooks that cover Foster Parent Finances and Health and Safety.

The Foster Parent’s Charter

The Scottish Government as yet has not published a specific Charter for Foster Parents but we have adopted the UK Government Charter.

‘Local authorities and fostering services must treat foster parents with openness, fairness and respect as a core member of the team around the child and support them in making reasonable and appropriate decisions on behalf of their foster child’

(Extract from Government’s Foster Parent Charter – the entire document with a Ministerial Forward can be downloaded here)

The Charter was introduced to ensure that foster parents are at the heart of arrangements for looked after children and are fully engaged, supported and consulted at every stage. Fosterplus endorses this Charter.

Trauma Informed Practice

Individual trauma results from an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional or spiritual well-being.

What is Trauma-informed Practice?

The development of Trauma-informed Practice (TIP) can be traced to the USA and to the ground breaking work of Maxine Harris and Roger Fallot (Harris & Fallot, 2001), and Sandra Bloom (Bloom S., 2013). Based on the models they developed, TIP is now widely understood as follows (Paterson, 2014):

Trauma-informed Practice

A model that is grounded in and directed by a complete understanding of how trauma exposure affects service user’s neurological, biological, psychological and social development.

As such, TIP is informed by neuroscience, psychology and social science as well as attachment and trauma theories, and gives a central role to the complex and pervasive impact trauma has on a person’s world view and relationships. It is applicable across all sectors of public service, including social care, physical health, housing, education, and the criminal justice system (Schachter, Stalker, Teram, Lasiuk, & Danilkewich, 2008; Havig, 2008; Cole, Eisner, Gregory, & Ristuccia, 2013). Trauma-informed organisations assume that people have had traumatic experiences, and as a result may find it difficult to feel safe within services and to develop trusting relationships with service providers. Consequently, services are structured, organised and delivered in ways that promote safety and trust and aim to prevent retraumatisation. Thus, trauma-informed services can be distinguished from trauma-specific services which are designed to treat the impact of trauma using specific therapies and other approaches.

Adapting an analogy used by Harris & Fallot (Harris & Fallot, 2001), the development of organisations that are trauma-informed is akin to the development of organisations that are disability-informed. The Disability Discrimination Act of 2005 states that organisations must make reasonable adjustments to their services and premises to ensure that disabled people can access them. As a result, buildings must provide access for people in a wheelchair, services need to provide written information in a variety of formats, and convenient parking must be provided for people with a disability. In this context, organisations were not required to deliver specific services to people with disabilities, but instead were required to make their services more accessible.

Why is it important to be trauma-informed?

A review of the literature provides evidence that trauma-informed practice is effective and can benefit both trauma survivors and staff. For trauma survivors, trauma-informed services can bring hope, empowerment and support that is not re-traumatising. Moreover, such services can help close the gap between the people who use services and the people who provide them (Filson & Mead, 2016).

‘I think one of the key benefits is about creating more empathy within staff. For some reason it just really hits a note with people and behaviours which they had… You know, they’ve been given some of this information before but it just draws it together, and it seems like quite a powerful way to help staff make sense of people’s presentation.’ (Mental Health)

‘Understanding distressing behaviour amongst pupils means a calmer school. More compassionate staff. Better-behaved children. More emotionally stable children. You can see their self-esteem begin to build … Attendance improved and exclusions dropped. Improved behaviour overall. Wellbeing language improved. Children’s confidence and self-esteem improves.’ Education

‘If you’re going to work in a trauma-informed practice approach, that actually benefits everybody because it actually then means that the people who are keeping all of that buried, who may be…you know, repeatedly presenting as physical complaints, that actually that then enables them. And actually, in the longer term, it actually means you provide better care…….. What I try and get across to people though is that if you do…if you apply trauma-informed practice approaches, then actually what that means is that over serial consultations,… you save time, people seem to feel better. And you get to where you need to with healthcare concerns.’ General Practice (GP)

Key principles

The key principles underlying TIP are listed below, adapted from Fallot and Harris (Fallot & Harris, 2006).

Key principles of trauma-informed practice

- Safety

Efforts are made by an organisation to ensure the physical and emotional safety of clients and staff. This includes reasonable freedom from threat or harm, and attempts to prevent further retraumatisation.

- Trustworthiness

Transparency exists in an organisation’s policies and procedures, with the objective of building trust among staff, clients and the wider community.

- Choice

Clients and staff have meaningful choice and a voice in the decision-making process of the organisation and its services.

- Collaboration

The organisation recognises the value of staff and clients’ experience in overcoming challenges and improving the system as a whole. This is often operationalised through the formal or informal use of peer support and mutual self-help.

- Empowerment

Efforts are made by the organisation to share power and give clients and staff a strong voice in decision-making, at both individual and organisational levels.

Although there may be differences in terms of their application, it is widely acknowledged that these principles are relevant across the public sector and its range of services. It is also recognised that the development of trauma-informed practice requires systematic alignment with these five principles, along with change at every level of an organisation. For this reason, the implementation of TIP is often described as an ongoing process of organisational change, requiring a profound paradigm shift in knowledge, perspective, attitudes and skills that continues to deepen and unfold over time (Alive and Well Communities Educational Leader’s Workgroup, 2014). Thus the literature increasingly refers to a ‘continuum’ of implementation, where TIP is a journey, not a destination.

Secure Base Model

What is a secure base?

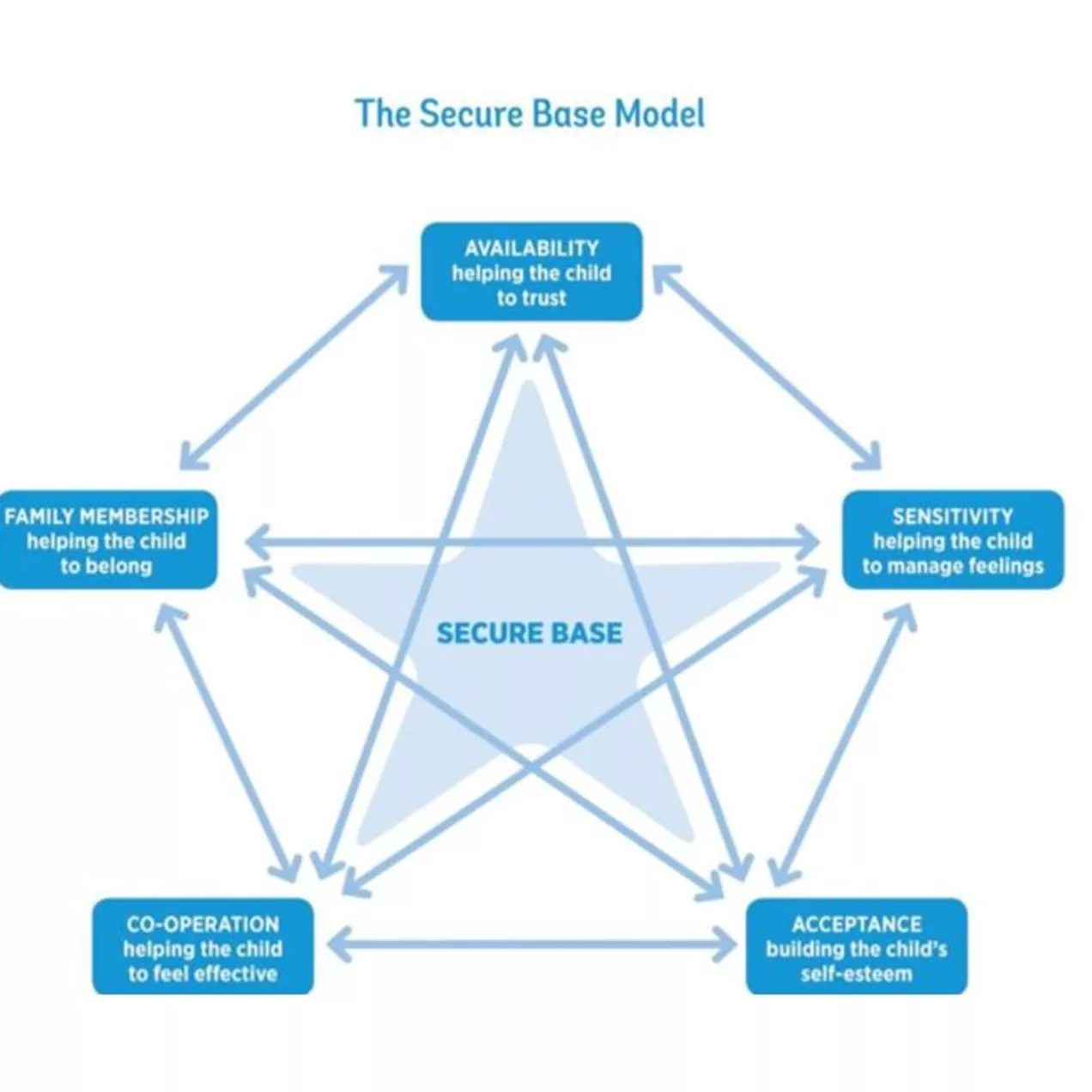

A secure base is at the heart of any successful caregiving environment – whether within the birth family, in foster care, residential care or adoption. A secure base is provided through a relationship with one or more caregivers who offer a reliable base from which to explore and a safe haven for reassurance when there are difficulties. Thus a secure base promotes security, confidence, competence and resilience.

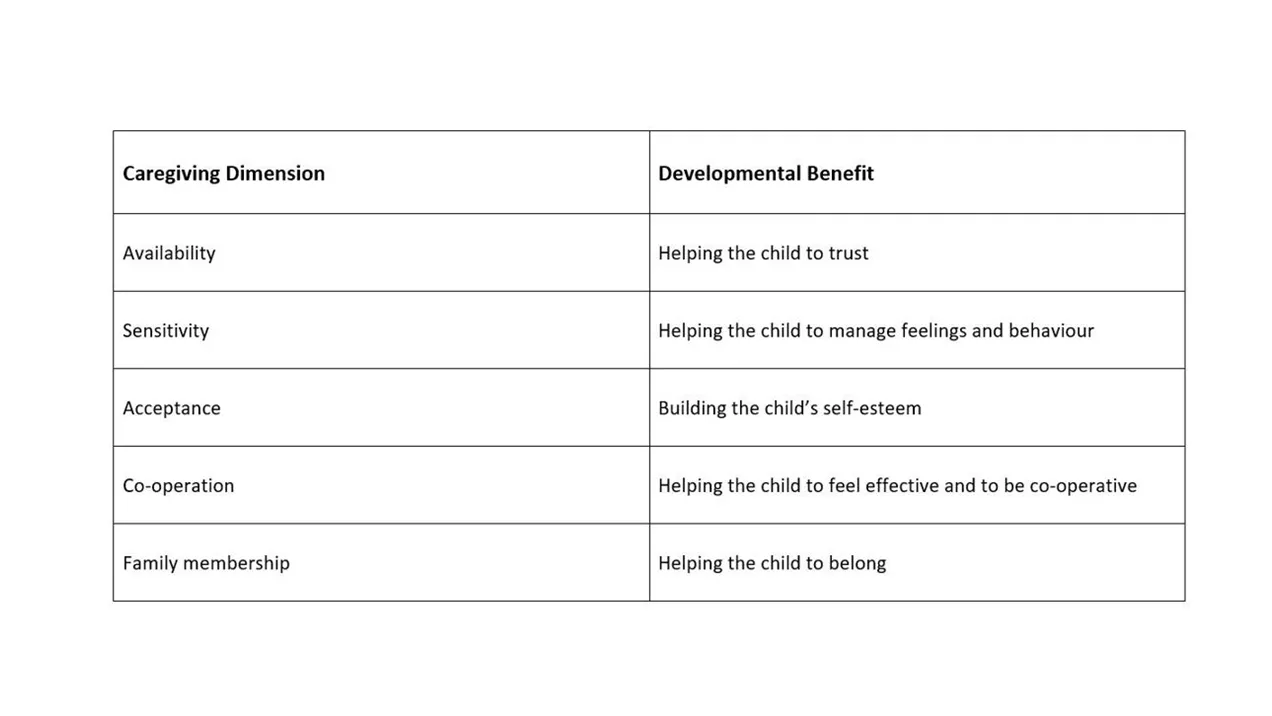

The Secure Base Model is drawn from attachment theory, and adapted to include an additional element, that of family membership, for children who are separated from their birth families. The model proposes five dimensions of caregiving, each of which is associated with a corresponding developmental benefit for the child. The dimensions overlap and combine with each other to create a secure base for the child, as represented below:

Fosterplus has adopted the concept of a secure base as central to our understanding of how children form relationships and develop, and the role of the foster parent as a primary caregiver. The model and the dimensions of caregiving are covered and referenced in foster parents’ preparation and post-approval training and are used as a framework for understanding children’s behaviour and relationship development in foster placement and forms of intervention by parents.

The Secure Base Model underpins the therapeutic foster care we ask our foster parents to provide. It has been developed through a range of research and practice dissemination projects led by Gillian Schofield and Mary Beek in the Centre for Research on Children and Families at the University of East Anglia.

The caregiving dimensions

For the purposes of the Secure Base Model, caregiver/child interactions are considered within five dimensions of caregiving. Each of the five caregiving dimensions can be associated with a particular developmental benefit for the child:

It is important to bear in mind that, the dimensions are not entirely distinct from each other. Rather, in the real world of caregiving, they overlap and combine with each other. For example, a caregiver who is playing with a child in a focused, child-led way may be doing so with sensitivity and acceptance as well as demonstrating availability and promoting co-operation.

Research (Beek and Schofield 2004) has demonstrated that, over time, positive caregiving across the five dimensions provides a secure base from which the child can explore, learn and develop.

What does secure base mean for foster parents?

The Secure Base Model provides a positive framework for therapeutic caregiving, which helps infants, children and young people to move towards greater security and builds resilience. It focuses on the interactions that occur between caregivers and children on a day to day, minute by minute basis in the home environment. But it also considers how those relationships can enable the child to develop competence in the outside world of school, peer group and community.

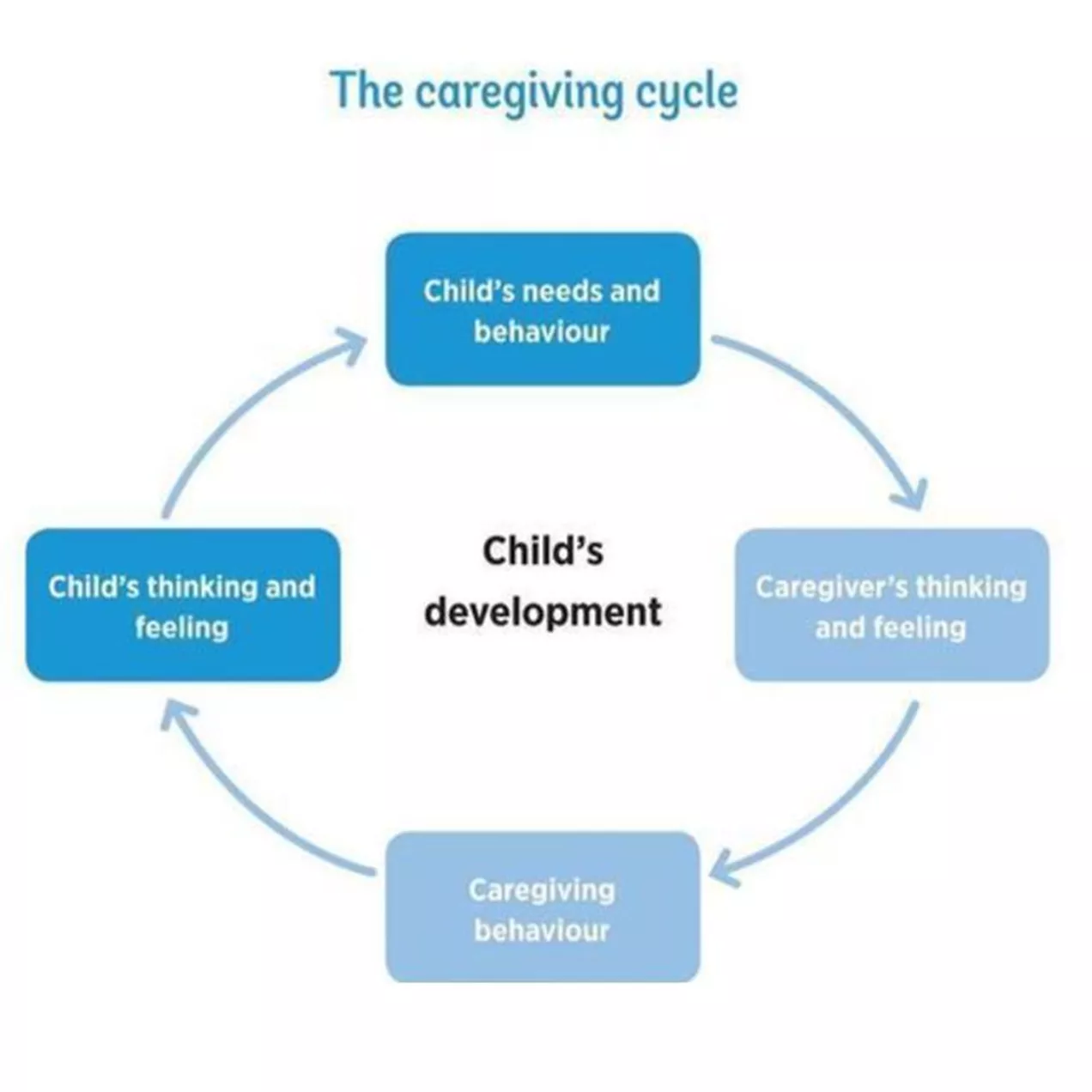

It can be helpful, first, to think about caregiver/child interactions as having the potential to shape the thinking and feeling and ultimately the behaviour of the child.

This cycle begins with the child’s needs and behaviour and then focuses on what is going on in the mind of the caregiver. How a caregiver thinks and feels about a child’s needs and behaviour will determine their caregiving behaviours. The caregiver may draw on their own ideas about what children need or what makes a good parent from their own experiences or from what they have learned from training. The caregiving behaviours that result convey certain messages to the child. The child’s thinking and feeling about themselves and other people will be affected by these messages and there will be a consequent impact on their development. This process can be represented in a circular model, the caregiving cycle, which shows the inter-connectedness of caregiver/child relationships, minds and behaviour, as well as their ongoing movement and change.

Secure Base Model – further reading for foster parents

The Secure Base Model has been developed through a range of research and practice dissemination projects led by Gillian Schofield and Mary Beek in the Centre for Research on Children and Families at the University of East Anglia. One of their publications is specifically targeted at foster parents and adopters:

‘Promoting Attachment and resilience: A guide for foster parents and adopters on using the Secure Base model’

https://corambaaf.org.uk/books/promoting-attachment-and-resilience

Getting it Right for Every Child

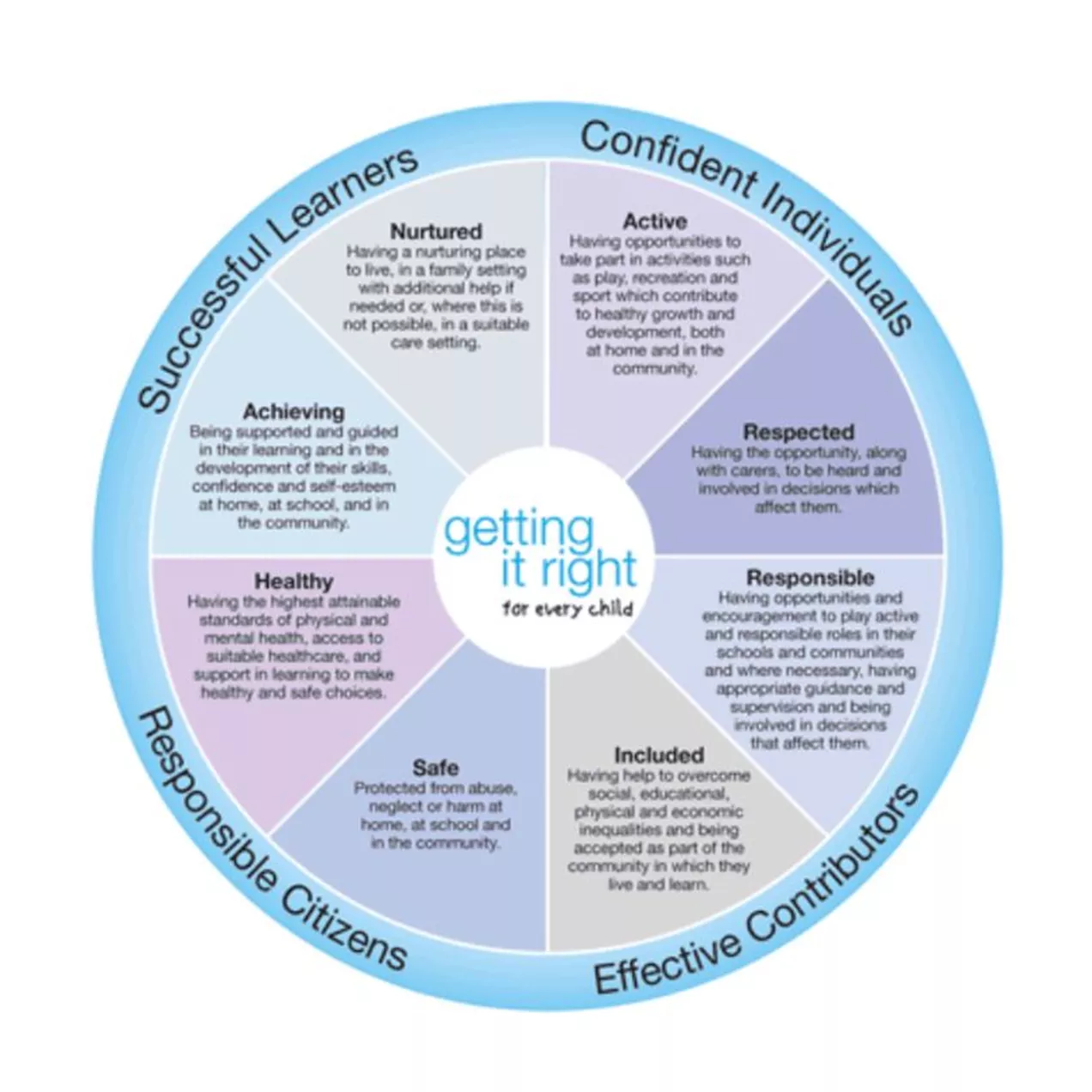

Getting it Right for Every Child or as it is often commonly referred to, GIRFEC has been the Scottish Government’s national approach for working with all young people in Scotland since 2010. Some of the elements of the approach are now embedded within the Children and Young People (Scotland) Act 2014. It is a model that looks at the way services are delivered to ensure that all of the child’s needs are being met and that we are working to help them be resilient and confident young people who have been encouraged and assisted to make the most of their abilities and strengths. This model looks at the whole world of the child and how we can evidence and demonstrate we are meeting their needs in relation to keeping them safe, and healthy; helping them to achieve their full potential, ensuring they feel cared for and nurtured; that they are leading active lives, and are respected for who they are; that they are shown and helped how to behave in a responsible way to themselves and others; and that they feel included both at home and in the community. You may hear this referred to as the SHANARRI wellbeing indicators.

The secure base model and GIRFEC are complimentary of one another and work well to help us create an environment that enables us to meet these essential needs in the children we care for.

Well Being Wheel is used to show that the whole world of the child, with them at the centre.

Further information on Getting it Right for Every Child (GIRFEC) can be found on the Scottish Government Website.

Policies and Procedures

There are a range of policies and procedures which govern the way we work within Fosterplus and these are uploaded onto CHARMS for ease of access. You will be able to use your CHARMS login to access these policies by clicking on Download on the Home menu bar.

In many places, this foster parent handbook only summarises or makes reference to policies and procedures that can be accessed in their full versions from CHARMS.

Foster Parent Finance Handbook

Fosterplus will issue its Foster Parent Finance Handbook, which sets out all matters in relation to payment terms and conditions for foster parents. This covers everything that foster parents will need to know about payments and allowances.

Health and Safety

Fosterplus has developed a separate health and safety handbook designed to raise awareness of health and safety in the home and therefore reduce the likelihood of accidents occurring.

We have both a legal and moral obligation to ensure that reasonable steps are taken to ensure the health, safety and welfare of our staff, the children, young people and families and any others we work with. Accordingly, regular health and safety assessments will be carried out to identify hazards and to ensure that appropriate measures are in place to reduce the risk to a reasonable level. If you move house it will always require for a health and safety assessment to be carried out shortly after you move.

The health and safety handbook supports this process by providing health and safety information and advice. It is also designed to raise awareness of health and safety in the home and to allow foster parents to become more involved in the process.

Learning and Development Programme

Learnative is the “One Stop Shop” for all your training & development. It provides dates of all training courses scheduled and all E-Learning courses available, including the local training programme, and it is updated regularly. All foster parents will have their own PDP plan and this will be reviewed regularly. Fosterplus complies with Regulations and Health and Social Care Standards and, as such, parents are required to participate in mandatory, core and on-going learning and development activities.

Fosterplus is passionate about learning and development, as we believe it can make a significant difference to the effectiveness of your role as a foster parent. We are committed to ensuring that foster parents receive the training they require to provide the best possible care and support to children and young people. It gives you both the tools and skills to meet the needs of children looked after, whilst building the knowledge that underpins your practice.

It will be possible for birth children, household members and members of the foster parent’s support network to attend some training courses

Our commitment to you is to provide the training and support to develop your skills and knowledge to provide a high quality service. Training is also a key to safeguarding children, foster parents and their families, by informing foster parents of how to care for children safely. Fosterplus values and appreciates the care and commitment you provide for the children and young people.

In recognition of this, the foster parent training programme offers opportunities to increase your professional development, meet with other foster parents and share experiences. If you need assistance accessing Learnative, please speak with your supervising social worker, the Training Assistant or the Learnative Team (01527 556484).

Glossary

Advocate – a person independent of any aspect of the service or any of the agencies involved in purchasing or providing the service, who acts on behalf of, and in the interests of the person using the service.

Allegation – an accusation of physical, emotional or sexual abuse, or serious neglect, of a child or young person.

Agency Decision Maker (ADM) – this is a senior person within the fostering service who makes a final decision on foster parents’ approval and terms of approval, taking into account any recommendations from a fostering panel.

Birth parents who hold parental responsibility retain their legal rights and duties for their child.

The Care Inspectorate – the Care Inspectorate is the government body responsible for inspecting fostering services in Scotland. All independent fostering providers have to be registered with the Care Inspectorate.

CAMHS – Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service. This service is part of the National Health Service and provides mental health assessments and services to children up to age 18.

Compulsory Supervision Order – a legal order that can be made through the Children’s Hearing system under the Children’s Hearing (Scotland) Act 2011.

Care Plan – every child in care should have a care plan which will include details about their needs, how these will be met, and contain information about their placement and the longer term planning for their care. The care plan will include a health plan, personal education plan and placement plan. Please note that often these are not written up as separate documents but are all integral to the care plan.

Child or Children - used to refer to all children under the age of 18 years (where the context specifically relates to older children, the term ‘young person’ is used).

Children’s Hearing - The Children’s Hearings System, a uniquely Scottish system, began operation on 15 April 1971. Initially children’s hearings were concerned mainly with children who had committed offences, but in the late 1970s reported incidents of child abuse increased and in the 1980s child sexual abuse began to be acknowledged as a widespread problem. The number of care and protection referrals to hearings has grown steadily over the years and now vastly outweighs offence referrals. Originally the hearing system operated under the 1968 Social Work (Scotland) Act which was amended by the Children (Scotland) Act 1995. The main legislation now governing the children’s hearing system is the Children’s Hearings (Scotland) Act 2011.

The 2011 Act also made a number of changes to the law by which a children’s hearing makes decisions:

- the grounds of referral were revised and modernised

- pre-hearing panels were created to make some procedural decisions in advance of the children’s hearing

- the legal orders panel members can make were simplified and modernised

- more flexibility was given to the interim decisions panel members can make

- changes were made to how a solicitor is available to assist a child, relevant person and certain others at a hearing

Children’s Panel - The role of a panel member is to make decisions in the best interests of the children and young people that come to children’s hearings, to help improve their lives. Before each hearing, panel members are sent reports and papers relating to the child or young person who will be attending the hearing.

A panel member is a lay tribunal member who volunteers to sit on children’s hearings. Panel members are people from the community who come from a wide range of backgrounds. Panel members should either live or work in the local authority area in which they sit on hearings. This ensures that they are familiar with the local area, in which the children and young people they see at hearings live. Panel members sit on hearings on a rota basis. Each children’s hearing has three-panel members and there must be a mix of men and women.

Children’s Reporter - The Children’s Reporter is the person who will decide if a child or young person needs to be referred to a children’s hearing. Children’s Reporters are trained professionals whose job it is to decide whether there are legal ‘grounds’ and whether a compulsory supervision order is necessary for the child. If so, the Children’s Reporter will arrange a hearing for the child.

Child’s Social Worker – this is a social worker who is provided by the responsible local authority to work with a child and to plan for their care. They are also responsible for visiting the child to ensure that their needs are being met.

Contact – Now referred to as family time.

Continuing Care – allowing young people who have reached the age of 18 to continue living with their former foster parents until they are 21, or beyond if the young person completes an agreed programme of education or training being undertaken on their twenty-first birthday. Local authorities now have a legal responsibility to support these arrangements under the Children and Young People (Scotland) Act 2014.

Corporate Parent – Under the Children and Young People (Scotland) Act 2014 the role of the corporate parent was more clearly defined in law and is much wider than previously held, which was predominantly the Local Authority but now includes health, housing and police and anyone with a responsibility to and for the child.

Corporate parenting as a concept exists to try and improve the outcomes and to improve the level of respect people have for the rights of care experienced and looked after children and young people. Corporate parent responsibilities are intended to encourage people and organisations to do as much as they can towards improving the lives of care experienced and looked after children, so that they:

- feel in control of their lives, and

- are able to overcome the barriers they face

Statutory Guidance on Part 9: Corporate Parenting:

Corporate parenting represents the principles and duties on which improvements can be made for these young people. The term refers to an organisation’s performance of actions necessary to uphold the rights and secure the wellbeing of a looked after child or care leaver, and through which physical, emotional, spiritual, social and educational development is promoted, from infancy through to adulthood. In other words, corporate parenting is about certain organisations listening to the needs, fears and wishes of children and young people, and being proactive and determined in their collective efforts to meet them. It is a role which should complement and support the actions of parents, families and foster parents, working with these key adults to deliver positive change for vulnerable children.

Deregistration of a Foster Parent – this is where a fostering service proposes to change the terms of approval of an existing foster parent without their agreement. If it is considered that a foster parent is no longer suitable to foster. The foster parents have 28 days in which to make representations to the fostering service. This also covers the resignation of a foster parent for their own personal reasons as they are also deregistered as foster parents when the panel is in receipt of their resignation.

Designated Teacher – all schools have a designated senior manager within the school who has an overview and a specific responsibility to support and promote the educational achievement of looked after children in a school. The senior manager should act as an advocate for the children, ensure the school has proper arrangements in place to work with the pupil, foster parent and social worker to make sure the child has a good quality personal education plan.

Emergency Placement – An unplanned placement made in an emergency where no other placement type has been identified by the local authority. (Under the LAC regulations 2009 an emergency placement must be reviewed by the LA within 3 days and may be extended for a period not exceeding 12 weeks.)

For a child this will mean that there are immediate concerns for their safety and wellbeing and they require to be removed from their home environment as quickly as possible while the care planning process establishes the best option for the child.

Family Time – the process whereby children stay in touch with people who have been important to them. These include relatives such as parents and grandparents, as well as others such as former foster parents. There are differing types of family time, such as supported, supervised and unsupervised. You will become familiar with the notion of family time when you have children in placement. Some children may have no contact whatsoever for their own safety/wellbeing.

Foster Parent / Foster parent - is a person who is approved as a local authority foster parent (this includes foster parents who have been approved by an independent fostering agency and foster parents who have been approved by the local authority).

Foster Parent Agreement – when a fostering service first approves a foster parent, they must enter into a written foster care agreement which covers a range of matters which are specified in the fostering regulations.

Fostering Panel – a fostering panel brings together a group of suitably experienced, knowledgeable and independent people, drawn from a central list held by the fostering service, who make recommendations on the approval of prospective foster parents and usually any changes to the approval of existing foster parents. The Looked After Children Regulations, 2009 cover the functions of a fostering panel and who can sit on one. Fosterplus also has one representative on each panel.

Fostering Panels, Regulations 17 to 20

- The panel should have a gender balance and individual panel members should be aware of equality and diversity issues. Issues of gender, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, family structure and disability may all emerge in relation to both those who wish to foster and to the children and families using the fostering service.

- The panel may be drawn from: staff within the social work service … existing experienced foster parents; adults who have experienced the care system, especially through foster care; … and independent individuals with relevant professional or specialist experience or knowledge.

Guidance on Looked After Children (Scotland) Regulations 2009 and the Adoption and Children (Scotland) Act 2007

Health and Social Care Standards – foster care and family placement services – Fostering services are subject to Health and Social Care Standards. They are used during inspections to check the regulations are being met. They are important as a guide to what fostering services should provide and do as a minimum, but the standards are intended to be qualitative, in that they provide a tool for judging the quality of life experienced by children in foster care. As such, services should always seek to exceed the minimum standards.

Host Authority – this is the authority that the foster parent lives and they may have a child from a different authority placed with them.

Interim Placement - A placement which has been in place for less than 24 months, not secured by a Permanence Order. There must be differentiation between interim placements which are:-

- Part of a concurrency plan

- Working towards rehabilitation with birth parents or foster parents (not part of a concurrency plan)

- Working towards a Permanence Order with a different foster parent

- Working towards an Adoption Order or Permanence Order with current foster parent (as per definition above)

For a child this means that the care planning process has concluded that they will benefit from spending some time being cared for away from home and there is a time linked plan for rehabilitation with parents or an alternative care placement is being sought.

Long Term Placement - A placement which has been in place for longer than 24 months but not secured with a Permanence Order. (This should be an exceptional situation and an indicator that the placement requires close scrutiny). There must be differentiation between long term placements where:-

- An adoption order is being sought

- A Permanence Order with authority to adopt is being sought

- A Permanence Order is being sought

- The child’s care plan indicates that the placement will be maintained into adulthood (18+ years of age) without a Permanence Order being sought

- The child’s care plan indicates that alternative placements are being sought (including with the birth family)

- The child’s care plan gives no indication of the placement objective or expected duration and therefore requires close scrutiny

Looked After Child – a child is looked after if they are in a local authority’s care because of a care order (including an interim care order) or if the child is provided with accommodation under Section 25 of the Children’s (Scotland) Act 1995, for more than 24 hours, with the parents’ agreement, or with the child’s consent if they are over the age of 16 years. Children who are placed away from home under an emergency protection order, made the subject of police protection or remanded into the care of the local authority by criminal courts are also looked after.

Looked After & Accommodated Review - also sometimes referred to as a ‘LAAC’ review. Purpose of this is to assess how far the care plan is addressing the child’s needs and whether any changes are required to achieve this. The frequency of reviews is set down in regulations, but, can be no less frequent than 6 monthly.

Matching – The process of linking an individual child with a particular foster parent who can best meet the needs of the child.

Parent – in regulations, this is a person who is the parent of the child, a person who is not the child’s parent but who has parental responsibility for the child or, where the child is in care and there was a residence order in force with regard to the child immediately before the care order was made, a person in whose favour a residence order was made.

Parental Responsibility – this is a concept introduced by the Children (Scotland) Act 1995 which describes the rights and responsibilities of parents towards their children. A court can also grant parental responsibility to others through legal orders – whereby it is shared with the parent/s, or in the case of adoption it transfers to the adoptive parent/s.

Parent and Child – placements for children with one or both parents (this will require the Form F Parent and Child Addendum).

Placement – an agreement for a child to stay with a particular foster family.

Placement Plan – the placement plan forms part of the child’s overall care plan and lays out how the placement will meet the particular child’s needs, in particular the day to day arrangements for his or her care, including delegated authority to the foster parent/s. This is usually contained within the child’s Care Plan rather than a separate plan. Throughout this document please note that the placement plan will not be separate document but form part of the care plan.

Permanent Placement – A placement secured by a Permanence Order for a child this means that the care planning process has concluded that they will thrive best if they are cared for away from home on a permanent basis. A Permanence Order, which is applied for by the Local Authority through the courts, can provide the local authority, child and their foster parent with legal security, the stability and the time for strong relationship bonds and a sense of belonging to develop.

PVG Check – (Protecting Vulnerable Groups); this is a check that is undertaken to discover if a person has an existing criminal record in the UK. PVG checks can include ‘soft’ information where no criminal charges have been brought but where there have been serious concerns raised. All foster parents will undergo a PVG check but members of your support network will undergo either an enhanced disclosure or basic disclosure. These checks are undertaken by Disclosure Scotland. Even although you may have a check in place that is required by your place of employment, Fosterplus will still ask for an updated to check to be undertaken.

Registered Fostering Services (RFS) – registered fostering services, such as Fosterplus, assess and approve foster parents in the same way as the local authority. In Scotland these services must operate as ‘not for profit’, Before a RFS can provide a fostering service to a local authority it must have formal arrangements with the local authority in place under the Looked After (Scotland) Regulations as amended by the Public Services Reform (Scotland) Act 2010. RFS are subject to external inspection by the Care Inspectorate and must take account of the Health and Social Care Standards for foster care and family placement services, as they will be inspected against them.

Definition of a Registered Fostering Service

It must be a voluntary organisation, in terms of section 7(6) of the Regulation of Care (Scotland) Act 2001. Section 77(1) of that Act says that ‘voluntary’ means it is not operated for profit. The requirement for a registered fostering service to be a voluntary organisation is repeated in section 59(3) of the Public Services Reform (Scotland) Act 2010.

Guidance on Looked After Children (Scotland) Regulations 2009 and the Adoption and Children (Scotland) Act 2007

Regulations – These are the Looked after (Scotland) Regulations 2009 and outline the legal requirements for foster care and all fostering services must comply with them. Failure to do so is a breach of the law.

Residential Children’s Home – for some children who need to be looked after, a family environment may not be suitable; in which case they will be cared for in a residential children’s home which provides 24 hour support and supervision.

Responsible Authority – this is the local authority that has responsibility for ensuring that the child is looked after appropriately while in its care. Sometimes referred to as the Placing Authority.

Scottish Government (SG) - The devolved government for Scotland has a range of responsibilities which include: health, education, justice, rural affairs, housing and the environment. Some powers are reserved to the UK government and include: immigration, the constitution, foreign policy and defence. Therefore all legislation in respect of children and young people for care, health and education and employment are devolved to the SG. The Scottish Government has a minister for Children and Young People.

Short Break - A placement which forms part of a planned series of short breaks (including emergency placements with a foster parent who is already providing planned short break placements to the child or young person).

For a child this will mean that because of special circumstances they and their foster parent will benefit from therapeutic services or periods of respite.

Supervising Social Worker - This is your allocated, qualified social worker who will support you and your family in every aspect of your fostering career with Fosterplus, whether you have a child in placement or not. They will carry out formal supervision sessions with you, visit the children you have in placement and ensure you are receiving all the necessary support to undertake your role fully and effectively.

Throughcare and Aftercare - As of 1 April 2015 local authorities have a statutory duty to prepare young people for ceasing to be looked after (‘Throughcare’’) and to provide advice, guidance and assistance for young people who have ceased to be looked after (‘Aftercare’’) on or after their 16th birthday. There is a duty on local authorities to provide this support up to the age of 19 and a duty to assess any eligible needs up to their 26th birthday, or beyond at their own discretion. This is embedded in legislation: The Children (Scotland) Act 1995 (as amended) and the Children and Young People (Scotland) Act 2014.

Unaccompanied Asylum Seeking Children (UASC) – a child under 18 who has entered the country without an adult who has parental responsibility for them and so is accommodated under Section 25 of the Children (Scotland) Act 1995 unless they have been made subject of any other legislation via the Children’s Hearing system.