Foster Parent Handbook

Chapter 6

Colour Code Key:

Fosterplus Policies, Procedures and Guidance

Legislation and Government Guidance

General Sources and Good Practice Information

The Child’s Wishes and Feelings

Expressing your views

“My views will always be sought and my choices respected, including when I have reduced capacity to fully make my own decisions.”

“If I am unable to make my own decisions at any time, the views of those who know my wishes, such as my foster parent, independent advocate, formal or informal representative, are sought and taken into account.”

Health and Social Care Standards: 2.11 and 2.12

Children’s Guides

Every fostering service must produce a written Children’s Guide, which includes:

- A summary of what the fostering service sets out to do for children

- How they can find out their rights

- How to contact Care Inspectorate, if they wish to raise a concern with inspectors

- How to secure access to an independent advocate

The supervising social worker ensures that every child (subject to age and understanding) receives an age appropriate copy of our Children’s Guide, at the point of placement. It is the responsibility of foster parents to go through this with children and young people and to explain the contents. Where a child requires it, we will make the guide available in translation or through suitable alternative methods of communication, such as pictures, tape recording etc. If foster parents think this is required, they should discuss it with their supervising social worker.

Participation of Children and Young People

Listening to children and young people – what is the role of foster parents?

Fosterplus has since its inception had a commitment to participation at all levels of the organisation including, involving stakeholders in shaping the development of the service provided. We will talk and listen to the users of our services and make changes where possible in light of what we learn.

Fosterplus Participation Strategy – can be downloaded from CHARMS/Download

It is essential that children and young people are empowered to communicate their views on all aspects of their care and support. Within a foster home, children should receive personalised care and be allowed to exercise reasonable choice and independence in the food they eat and are able to prepare, clothes and personal requisites they buy etc. This should happen within reasonable limits set by each foster family.

Foster parents can play an important role in helping children and young people to take up issues with Fosterplus or their local authority, and can also help children understand how their views have been taken into account or to understand why their wishes or concerns have not been acted upon.

Fosterplus young people’s participation groups

Each local Fosterplus office runs a range of structured activities for young people of different ages, usually during school holidays. There are also participation groups where young people can meet together to share experiences and contribute their ideas to the running of Fosterplus. Your local office will keep you informed of events being organised.

Independent Advocacy Services

“I am supported to use independent advocacy if I want or need this.”

Health and Social Care Standards: 2.4

Why might a child need an advocate?

Foster parents are often the best champions for the children they care for and you should certainly see your role as that of a ‘pushy parent’ when it comes to dealing with services such as Education and Health; but sometimes you may not be in the best position to advocate for a young person. For example, a child or young person may wish to express dissatisfaction with their foster parent or their social worker and, in some situations, foster parents will feel unable to represent the child’s wishes and views as they may conflict with their own.

Children also may feel that they are not being listened to and that adults are making major decisions about their lives without treating their views seriously. They may not feel confident enough to challenge adults on their own, or may not know the right way to make sure their views are heard and acted upon.

What does an independent advocate do?

The role of an independent advocate is to support young people in making sure their views are properly represented, either by enabling the young person to speak for themselves or speaking on their behalf. All local authorities are required to provide independent advocacy schemes to which foster children must have access. It is very important that foster parents ensure that the children in their care are aware of their right to advocacy services and actively encourage them to use such services.

How does a child or young person access an advocate?

The welcome pack given to all young people when they come into the care of Fosterplus contains information regarding advocacy services such as the Children’s Rights Officer and Who Cares? Scotland; there is also information on how to give feedback about the service; It is important to bring this to their attention. Their local authority social worker should also be ensuring they have the information they need.

Children and Young People’s Commissioner

The role of the Children’s Commissioner in Scotland has a duty to promote and protect the rights of all children in Scotland in accordance with the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child.

Children and young people from all over the Scotland helped choose Bruce Adamson as their current Commissioner. They interviewed him about how he would help young people know more about their rights and found out his plans for the job by asking him lots of questions.

It is his job to make life better for all children and young people by making sure their rights are respected and realised and that their views are taken seriously.

He and his team looks after the rights of

- Everyone in Scotland under 18

- Everyone in Scotland under 21 who has been looked after or in care

There are various ways of making contact with the Commissioner either on line, by phone or text. There is also a link on their website with HAPPY TO TRANSLATE which is a unique and innovative national scheme which bridges communication gaps between organisations and service users who struggle to communicate in English.

Children & Young People’s Commissioner Scotland

Children and Young People’s Commissioner Scotland

Bridgeside House

99 McDonald Road

Edinburgh EH7 4NS

Tel: 0131 346 5350

Contact can be made by an online email service at

Web: https://www.cypcs.org.uk/contact/

Young People’s Freephone: 0800 019 1179

Or by Text 0770 233 5720 Texts will be charged at your standard network rate

In addition, there is the national CHILDLINE help line who can be contacted confidentially on 0800 1111 – the service is free and fully confidential and young people can contact them anonymously if they wish for information, advice or guidance.

Child’s Identity

Promoting a positive identity and valuing diversity

Identity and Heritage

“I am supported to be emotionally resilient, have a strong sense of my own identity and wellbeing, and address any experiences of trauma or neglect.”

Health and Social Care Standards: 1.29

Many looked after children have low self-worth and a very poor sense of their own identity. Many come from families that are subject to multiple problems and marginalisation. The Human Rights Act 1998, the Equalities Act 2010, the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, as well as the Children (Scotland) Act 1995 all require that every individual child who is looked after should be cared for in a way that respects, recognises, supports and celebrates their identity and provides them all with care, support and opportunities to maximise their individual potential.

UN Convention on the Rights of the Child

The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child can be downloaded via the UNICEF website at: http://www.unicef.org/crc/

Equal opportunities

Fosterplus is committed to a positive policy of equal opportunities in the delivery of its services to children and foster parents, employment of staff and recruitment of foster parents. We will actively oppose all forms of discrimination carried out on the grounds of age, disability, gender reassignment, marriage and civil partnership, pregnancy and maternity, race, religion or belief, sex, and sexual orientation.

All foster parents and staff will receive training on equality and diversity practice and expectations.

Trans-racial and trans-cultural placements

Fosterplus believes that a child’s racial and cultural background is fundamental to their identity and needs to be maintained and encouraged. Foster parents have a key role to play in enabling young people to feel secure in their sense of identity. This will often be best achieved through placements into families with same or similar racial and cultural backgrounds.

Where such placements are not available, it may still be in the child’s better interests to place them with a family from a different racial or cultural background. We recognise that an important principle in working with children from different cultures is to acknowledge that this requires special commitment, knowledge and skills, which need to be developed if young people of differing ethnic and cultural backgrounds are to grow up with a positive image of themselves.

Fosterplus will offer training, support, information and guidance for foster parents and social work staff to enable them to meet the needs of each child, and to maintain a commitment to equal opportunities. Foster parents are expected to undertake the mandatory training course Equality and Diversity within their first year of approval by the agency.

We also record and monitor the ethnicity, religion and spoken languages of children referred to us and placed with our foster families, as well as those who enquire about fostering with us. This data is used to inform the continuing development of services that meet the cultural and racial needs of foster children.

Promoting cultural identity

The practical ideas that follow have four important aims:

- To promote the child’s cultural identity.

- To give the child positive images of their identity.

- To prepare the child for the society in which they will be growing up.

- To learn about and share in the child’s culture.

The following is a list of some of the ways in which foster parents and social workers can actively involve themselves in any foster child’s culture, whether or not they share the same culture with them. The list is by no means definitive and each idea does not apply to all cultures, but it does include some important suggestions:

- Find out about special dietary rules.

- Find out about essential cultural customs, like hair and skin care.

- Make sure you have a stock of appropriate toys, books, etc.

- Find out about the rules of religious observance.

- Involve the foster family and the child with other families who reflect the child’s heritage.

- Encourage the child to keep contact with members of their original community, (the foster parents and their family should also meet them, where this is appropriate).

- Learn about the historical foundations of the child’s culture and share these with the child.

- Make contact with the local black or other minority ethnic community and attend social events with the child.

- Be aware of racism in the language you use and examine your attitudes to it. Help the child find ways of coping with it.

- Encourage the reading of black literature and the watching of television programmes directed towards ethnic minorities.

- Encourage mother-tongue speaking and learning.

Foster parents must respect parents’ wishes and encourage all children to value their background. Foster parents should aim to care for the child in accordance with the parents’ views. Birth parents may be greatly distressed if their child breaks food laws or the observances of religion.

Making these efforts will show children in care that their foster parent and their social worker value their culture, and that any differences between them are manageable. The efforts will be rewarded by a much more real understanding of the child in your care. Foster parents can probably think of many ways in which they can involve themselves in a child or young person’s culture. On the other hand, if the culture is very unfamiliar to them it may feel daunting, and if foster parents are not sure about how to go about seeking advice and making contact with their local black African, Asian, or other minority ethnic community, they should expect help, advice and support from the child’s social worker, and their supervising social worker.

Religion

We expect foster parents to care for a child’s spiritual and moral well-being as well as their physical and emotional development. Foster parents must not impose their own religious beliefs upon children and young people, even where the child may not declare themselves to be of any particular faith; but making them familiar with different beliefs may help them to develop their own ideas as they get older.

Information about a child’s religious beliefs should be provided by the child, his/her parents and/or social worker at the beginning of a placement and detailed in the placement plan, so that there is a clear understanding of expectations with respect of religion. This includes the religious background of a child’s family, the rules of religious observance, and the expectations regarding attendance at a place of worship.

Foster parents may need to take a child to and collect them from a place of worship, and must be prepared to do this. Foster parents should actively familiarise themselves with the values and practices of the child’s religious faith so that, for example, important dates in the child or young person’s religious calendar can be observed.

Dealing with discrimination

Children and young people may respond to prejudicial attitudes and discrimination by feeling ashamed, angry, rejected, and it may lower their sense of self-worth. For them to feel comfortable, foster parents and social workers need to feel comfortable too. Foster parents and social workers should help the child or young person to understand the nature of prejudice and prepare them to meet it and support them when they have to cope with it. It is a shared duty to take positive action to combat discrimination on the grounds of culture, religion, ethnicity or language.

Birth certificates

If a birth has been registered then a birth certificate is available recording the details of the child’s birth. If a copy of a child’s birth certificate is required, foster parents should contact the child’s social worker or seek advice from your supervising social worker.

Passports

Many foster children do not have a passport at the point they are first looked after. It is important that the potential for holidays and other trips abroad (e.g. school trips) is covered in the placement plan and that there is clarity about how a passport is to be obtained. This will be the responsibility of the child’s social worker and the United Kingdom Passport Agency provides guidance for social workers seeking to obtain a passport for a looked after child.

Where there are already plans in place for a holiday or other trip and the child does not have a passport, it is best to formally request that a passport be obtained as a matter of urgency. The written request should go to the supervising social worker to be passed on to the responsible authority, and should include:

- The reason for the request.

- The wishes of the child.

- The views of the parent/s, if known.

- The views of the foster parent/s.

The child’s social worker should obtain and complete the necessary application for the child or assist the child to complete the necessary application form.

If the child/young person is accommodated, their parents must be consulted with a view to obtaining their agreement. In such instances, good practice would suggest that involving the parent in the passport application process is recommended. Should the parent/s refuse to give consent and this is deemed unreasonable, then the child’s social worker may have to take advice from their Legal Services.

Life story work

What is life story work?

Children who live with their birth families generally have plenty of opportunity to know and learn about the events in their lives. These children generally grow up surrounded by their family members and they accept and feel secure about their place in the family. Their knowledge of who they are is built up from personal memories – good and bad – photographs, anecdotes and family folklore. All this is the foundation on which people build their self-image and become a secure adult.

All children are entitled to accurate information about their past and their family, but children separated from their birth families are often denied this opportunity. Many children come to blame themselves for being separated from their families and believe they are unlovable. Some children, particularly young children, can seem to live in the present and to forget the past. If a child has had a particularly unhappy time, foster parents and local authority social workers may also be tempted to try to protect them by encouraging them to forget the past. Though some memories will fade in the long term, curiosity – the deep need to know about their parents and understand their history in search of their true identity – will almost certainly surface, particularly when children are in their teens.

Compiling facts about their lives, and the significant incidents and the people in them, helps children to begin to understand and accept their past and move forward into the future. Life Story Work is a way of identifying and capturing the child’s past both by collating material such as photos, videos, mementos and written records, but also writing down people’s recollections of the child. Such information can be kept in a Life Story Book and Memory Box. The child’s social worker usually undertakes the sensitive task of compiling a life story book with the child, often in collaboration with the foster parent who has an important role in gathering material for the book.

The other important task for foster parents is to talk with the child in a way they can understand, about the fact they are not living at home and the reasons for this. It will be important for the foster parents to give them words to help explain their present circumstances and to allow them to accept those circumstances.

In summary, life story work can help the child feel comfortable with their past and reinforce their sense of identity and worth.

Ways to gather information for life story work

Written information – keeping regular records about the child’s development: when they walked and talked; what toys they liked; what food they liked etc. When deciding on what information to store in trust for the child, it is a good idea to think about the sorts of things your own children asked you about when they were younger. Also record factual information, such as full address of the playgroup or school attended.

Photographs and/or videos – taking these on a regular basis and on special occasions. It is important that, however brief, you take pictures of the child’s time in your family. Photographs of the foster parents and their family, foster home, child’s school and friends, pets, and of the child’s parents and family, may all be very important in the future. Take photographs of favourite activities, significant incidents, holidays, birthdays, weddings, parties and religious festivals. Write the date, location and names of people in the photo on the back. NB: Polaroid and computer generated photos fade. Use regular film and/or retain photos in digital format.

If children are reluctant to have their picture taken, then please respect this. Usually, with time and the excitement of an event, this self-consciousness passes. It is always possible that children may be reticent to have photographs taken because this was part of their previous abuse by an adult.

Mementos – keeping mementos of places visited, holidays shared, some playgroup pictures, school reports and so on. Retain certificates from school, sporting or educational awards, and anything else you or the child feel is important. These offer tangible evidence that the child had many experiences and provide a record of them.

Records of family time with birth families – keeping information about their family: from what they look like to what they were good and bad at. This is especially important if the child is not returning home, because it may eventually help them understand why this was not possible.

What happens to the life story book?

The life story book and other information in a memory box belongs to the child and should go with them when they leave a foster home. At the point a child or young person is moving on, you should discuss with the supervising social worker the best way to pass on information held in a memory box and/or life story book.

Children’s Behaviour and Relationships

Self-Regulation and Behaviour Management Training

In addition to the Secure Base Model, Fosterplus has also introduced a positive behaviour support training programme called Self-Regulation and Behaviour Management:

- Support foster parents and other involved professionals in developing knowledge and skills in positively responding to challenging behaviour.

- Promote the on-going development of resilience, de-escalation skills and confidence in children, young people and their foster parents.

The importance of secure base

The Secure Base Model provides a positive integrated framework that underpins Fosterplus’s practice, service delivery and learning. We have been running Introduction to The Secure Base Model programmes for both foster parents and support staff since 2016. This has included the senior leadership team, all managers, social workers and administrators, reflecting a shared vision and ambition to embed the secure base model throughout the organisation at every level. This is about building on and developing the foundations from which we all support, understand, share experience and improve the ordinary life experiences and chances of the children and young people who live within our service.

A secure base is at the heart of any successful caregiving environment – whether within the birth family, in foster care, residential care or adoption. A secure base is provided through a relationship with one or more caregivers who offer a reliable base from which to explore and a safe haven for reassurance when there are difficulties. Thus a secure base promotes security, confidence, competence and resilience.

Understanding children’s behaviour

Many children who are fostered have had experiences that give them little reason to trust adults. They have developed behaviours based on a need to try to protect themselves and to control their relationships and environments. Attachment theory suggests that exposure to warm, consistent and reliable caregiving can change children’s previous expectations, both of close adults and of themselves. The role of adults who can provide secure base caregiving, therefore, is of central importance.

The Secure Base Model provides a positive framework for therapeutic caregiving, which helps infants, children and young people to move towards greater security and builds resilience. It focuses on the interactions that occur between caregivers and children on a day to day, minute by minute basis in the home environment. But it also considers how those relationships can enable the child to develop competence in the outside world of school, peer group and community.

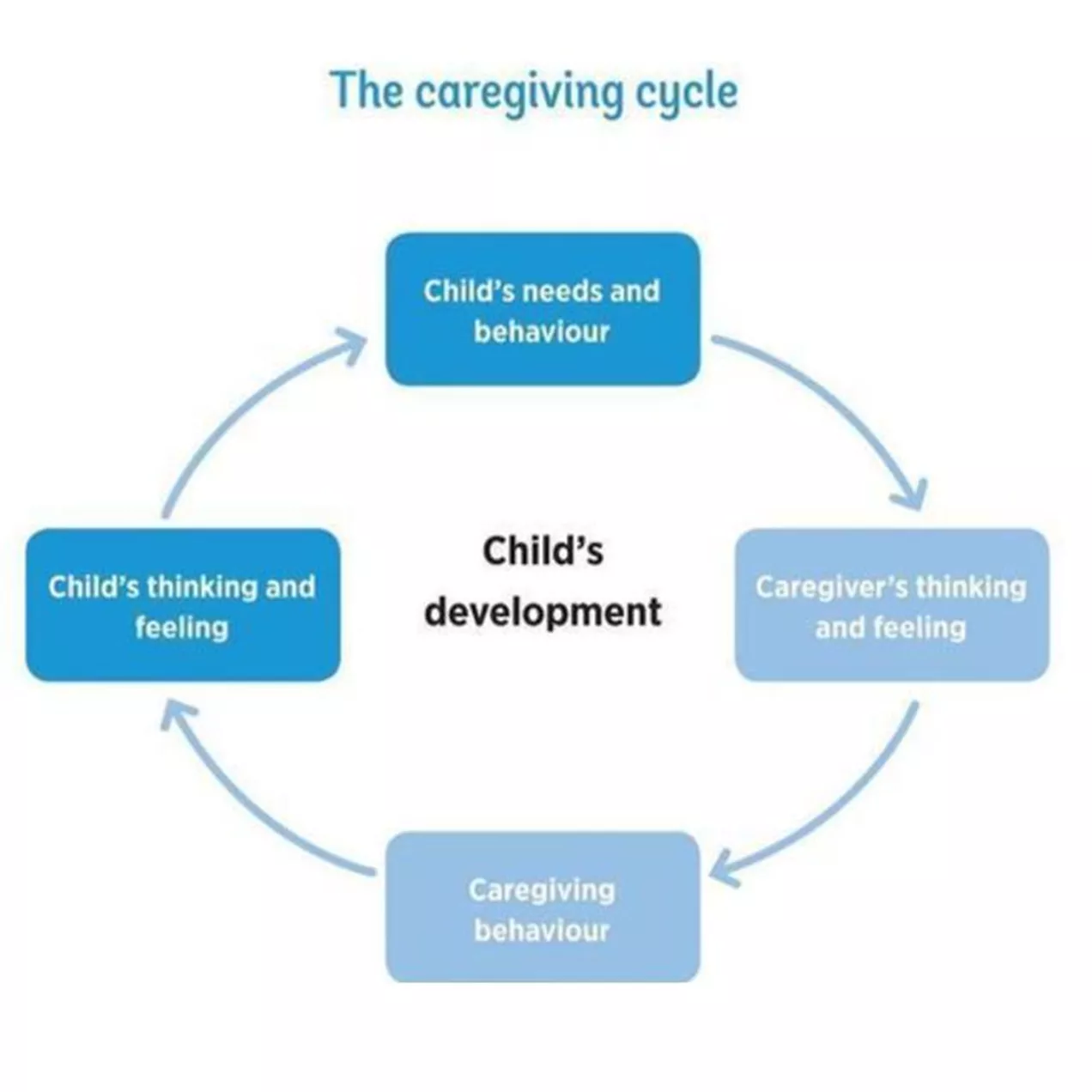

It can be helpful, first, to think about caregiver/child interactions as having the potential to shape the thinking and feeling and ultimately the behaviour of the child.

This cycle begins with the child’s needs and behaviour and then focuses on what is going on in the mind of the caregiver. How a caregiver thinks and feels about a child’s needs and behaviour will determine his or her caregiving behaviours. The caregiver may draw on their own ideas about what children need or what makes a good parent from their own experiences or from what they have learned from training. The caregiving behaviours that result convey certain messages to the child. The child’s thinking and feeling about themselves and other people will be affected by these messages and there will be a consequent impact on his or her development. This process is represented in a circular model, the caregiving cycle, which shows the inter-connectedness of caregiver/child relationships, minds and behaviour, as well as their ongoing movement and change.

Information and support to foster parents around behaviour

Foster parents must be given all the relevant information about the child or young person placed with them to help them to provide a secure base, build positive relationships and manage behaviour. This must include information about previous challenging behaviour and advice about how this might be handled in the future. If this is not provided by the child’s social worker, the supervising social worker will follow this up.

The child’s placement plan must set out any specific behavioural issues that need to be addressed or approaches to be used.

Research tells us that it is of great importance for foster parents to realise and build on whatever strengths and abilities (‘resilience’) a child has. The Secure Base Model emphasises the critical role the foster parent (‘caregiver’) can have in creating the best possible environment for a child to build on and develop their resilience, by thoughtfully offering:

- Availability – Helping the child to trust

- Sensitivity – Helping the child to manage feelings and behaviour

- Acceptance – Building the child’s self-esteem

- Co-operation – Helping the child to feel effective and to be co-operative

- Family membership – Helping the child to belong

Availability – Approaches for helping children to build trust

N.B. It is important to choose only activities that the child is likely to accept and enjoy.

- Day-to-day activities

- Establish predictable routines around mealtimes, getting up and going to bed.

- Ensure that the child always knows where to find you when you are apart.

- Manage separations carefully, with open communication about why it is happening, how long it will be and clear ‘goodbyes’ and ‘hellos’.

- Use calendar or diary chart to help the child predict and anticipate events.

- Ensure that the child feels specially cared for and nurtured when ill, hurt or sad.

- Be ‘unobtrusively available’ if the child is anxious but finds it hard to talk or accept comfort (for example, suggest a ride in the car).

- Offer verbal and non-verbal support for safe exploration.

- Building trust when caregiver and child are apart.

- Allow child to take small item or photo from home to school.

- Use mobile phone or text to help child know that you are thinking of them.

- Place small surprise on child’s bed when he is at school to show you have thought about them during the day.

- Keep a ‘goodies tub’ in the kitchen and put small treats in it for child to have in the evening.

- Activities that help children to think about trusting.

- Ask child to draw a fortress or make one in clay or sand. Child may choose miniature toys or animals to stand for the main people in his life. Ask child to show and talk about which ones he would let into his fort and which ones he would keep out and why (from Sunderland 2000).

- Ask child to draw a bridge with themselves on one side and someone they trust on the other. Ask them to draw a speech bubble coming out of their mouth and write in it what they are thinking or saying. Do the same with the other person (from Sunderland 2000).

Games and activities that help to build trust:

- Hand holding games such as ‘ring a roses’.

- Clapping games.

- Reading stories with child on lap or sitting close.

- Leading each other blindfold.

- Face painting.

- 3-legged race.

- Throwing a ball or beanbag to each other.

- Bat and ball.

- Blowing and chasing bubbles together.

- Rocking, singing, gently holding child.

- Rub lotion onto each other’s hands and arms.

- Brush and plait hair, paint nails.

- Teaching a new skill or learning one together.

(Source: Providing a Secure Base, Gillian Schofield and Mary Beek, University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK)

Sensitivity – approaches for helping children to manage feelings and behaviour

N.B. It is important to choose only activities that the child is likely to accept and enjoy.

- Observe child carefully – perhaps keep a diary, note patterns, the unexpected etc. Try to stand in the child’s shoes.

- Anticipate what will cause confusion and distress for the child and avoid if possible.

- Read cues for support and comfort – be aware of ‘miscuing’.

- Express interest, at a level that is comfortable for the child, in his/her thoughts and feelings.

- Provide shared, pleasurable activity and a ‘commentary’ on the feelings experienced by self and child.

- Find time for interactions that promote synchrony of action, experiences, expressions of feeling (simple action rhymes and songs, clapping games for younger children, ball and beanbag games, learning a dance together, building or making something together, share an ‘adventure’ or new experience together, a game that involves a shared experience of both winning and losing).

- Make a ‘me calendar’ to help a child to see and remember what is going to happen next.

- Collect tickets, pictures, leaflets, stickers etc. and make an ‘experiences book’ to help a child to remember and reflect on positive events.

- Name and discuss feelings in everyday situations (happy, proud, sad, confused, angry, worried, peaceful, excited, guilty, lonely, pleased, etc. Also discuss mixed feelings and feelings that change over time.

- Play ‘sensory’ games (involving touch, sound, smell, observation).

- Use clay, paint, crayons to express feelings.

- Use play and real examples to make sense of the world, how things work, cause and effect.

- Encourage children to stop and think before reacting.

- Help children recover/repair the situation/make things better after losing control of feelings – praise them for doing this.

- Use stories or puppets to develop empathy in the child – ‘poor owl, how does he feel now his tree has been cut down’, etc.

- Use television programmes/films to focus on why people feel different things and how they can feel different things at the same time.

- Speculate on and give names to the possible feelings of others in everyday conversations.

(Source: Providing a Secure Base, Gillian Schofield and Mary Beek, University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK)

Acceptance – approaches for building self esteem

N.B. It is important to choose only activities that the child is likely to accept and enjoy.

- Praise child for achieving small tasks and responsibilities.

- Provide toys and games that create a sense of achievement.

- Liaise closely with nursery and school to ensure a sense of achievement.

- Use positive language. For example, ‘hold the cup tight – good, well done’, rather than ‘don’t drop the cup’

- Offer a brief explanation of why behaviour is not acceptable and a clear indication of what is preferred. For example: ‘If you shout it’s really hard for me to hear what you want to say. I want to be able to hear you, so please talk in an ordinary voice’.

- Help child to list and think about all the things they have done that they feel proud of.

- Help child to think about times, events, occasions when they felt valued and special. Use photos and other mementos to record these events.

- List alongside child, all the things that make you feel proud of them. Can include acceptance of limitations (e.g. a time when the child tried but did not succeed at something, was able to accept loosing etc.).

- Encourage child to draw, paint, make a clay model or play in music how it feels when they feel good about herself. Do the same for yourself.

- Suggest that child lies on the floor, draw round the outline of the child’s body. Encourage the child to make a positive statement about different parts of herself (I’ve got shiny brown hair, a pretty T shirt etc.) and write or draw these onto the figure. Take this at the child’s pace and ensure the child feels comfortable with the statement made.

- As a family group, suggest that each person in the family writes down one good thing about all other family members, so that each child gets given a set of positive things about themselves.

- Make a poster with the child of ‘best achievements’.

- Ask child to teach you something that he is good at – such as a computer game or a joke.

- Buy a small treat and place it in the child’s bedroom as a surprise.

- Discover and support activities and interests that the child enjoys and can be successful in. May need active support (liaison with club leader, becoming a helper at the club etc.).

- Use dolls, toys, games and books that promote a positive sense of the child’s ethnic, religious and cultural background.

- Ensure that the child’s ethnic, religious and cultural background is valued and celebrated within the household.

- Model the acceptance of difference in words and behaviour.

- Model a sense of pride in self and surroundings.

- Model within the family that it is OK not to be perfect, that no one is good at everything but everyone is good at something.

(Source: Providing a Secure Base, Gillian Schofield and Mary Beek, University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK)

Co-operation – approaches for helping children to feel effective – and be co-operative

N.B. It is important to choose only activities that the child is likely to accept and enjoy.

- Find individual activities that the child enjoys and that produce a clear result. For example, give the child a disposable camera to use on holiday or on a day out, help them to get the photos developed and give them a small album for the results.

- Within the house and garden, minimise hazards and things that child cannot touch and keep ‘out of bounds’ areas secure so that the child can explore without adult ‘interference’ when he is ready to do so.

- Suggest small tasks and responsibilities within the child’s capabilities. Ensure recognition and praise when achieved. If they become an issue, do them alongside the child – a chance to show availability.

- Introduce toys where the action of the child achieves a rewarding result. For example, pushing a button, touching or shaking something.

- Make opportunities for choices. For example, allow child to choose the cereal at the supermarket, a pudding for a family meal, what to wear for a certain activity.

- Ensure that daily routines include time to relax together and share a pleasurable activity.

- Respond promptly to child’s signals for support or comfort or reassure an older child that you will respond as soon as possible. For example ‘I must quickly finish what I am doing and then I will come and help you straight away’.

- Do not try to tackle several problem areas at any one time. Set one or two priorities and work on them gradually until there are sustained signs of progress. Ensure that these are acknowledged.

- Use co-operative language wherever possible. For example ‘Would you like to come and have a sandwich after you’ve washed your hands’, rather than ‘Wash your hands before you eat your sandwich’.

- Find shared activities that the child enjoys and that produce a clear result. For example, baking cakes.

- Introduce games. State clearly when you have had enough and suggest alternative activity.

- Seek opportunities for the child to co-operate with other children – you may need to be present so that this is managed successfully.

- Help the child to identify a target that they would like to achieve, do, change etc. Settle on one where something done now will make a difference. Discuss what the young person can do and negotiate simple, relevant and achievable steps that they can take. When agreed, draw a simple staircase and write one task in each of the bottom steps of the staircase. For example, if the target is ‘go to see Manchester United play at home’, steps might be – use internet to find out dates of home games this season, settle on suitable date and put on calendar, find out train times, etc. Set a time to review progress and think about further steps needed.

(Source: Providing a Secure Base, Gillian Schofield and Mary Beek, University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK)

Family Membership – approaches for helping children to belong

N.B. It is important to choose approaches for helping children to belong that are suitable for the individual child and the plan for this child.

Belonging in an adoptive family, foster family or residential group

- Explain to the child from the beginning how the family/group works – its routines and expectations, its choice of food and favourite television programmes – so that the child can see how to fit in.

- Adapt those routines where possible and reasonable to accommodate the child’s norms and help the child feel at home e.g. meal times or bedtime.

- Have special places for the child in the home e.g. a hook for the child’s coat; a place at the table; the child’s name on the bedroom door or in fridge magnets on the fridge; bedding and bedroom decoration (posters etc.) that reflect the child’s age and interests.

- Promote family/group mealtimes and activities (e.g. going bowling) where the child can feel fully accepted as part of the family/group.

- Ensure extended family members and friends/all staff members welcome the child and treat the child as one of the family/part of the group.

- Have photographs of the child and of the child with the foster or adoptive family or residential caregivers on display – alongside photographs of other children who have lived in the foster or adoptive family or residential unit and moved on/grown up.

- Use memory and experience books of events and feelings about events during the child’s stay to build a family story to help the child be able to reflect on the meaning of family/group life and, if the child moves on, to take home to the birth family or to a new placement.

- Make sure the school knows (and the child knows that the school knows) that you are the family/residential unit caring for the child and need to be kept informed of any concerns but also of things to celebrate.

- Plan family/group life and talk about plans that will include the child, even if this is just an expectation that they will all go swimming together next week.

- Belonging to the birth family when separated.

- Develop or build on an existing life story book that contains information, pictures and a narrative that links the child to birth family members and birth family history. Ensure that it includes key documents e.g. copy of birth certificate, provides a full and balanced picture (see also Chapter 12) and is nicely presented, robust, valued and cared for. Even children who return to birth families benefit from making sense of complex family histories and their place in the family.

- Have photographs of the birth family where the child would most like to put them, e.g. bedroom or living room.

- Ensure that conversations about the birth family happen appropriately and are carefully managed within the family/group, so that the child does not have to make sense of negative, contradictory or idealised ideas about the birth family.

- Where direct or indirect contact is occurring, be actively involved in planning and facilitating contact so that the child’s welfare is paramount and contact promotes security as well as roots and identity.

- Managing memberships of more than one family.

- Adults need to demonstrate their own flexibility about children’s family memberships and what they might mean to the child.

- Both informally and in a planned way, talk with the child about the benefits and the challenges of having more than one family and help the child to understand and manage these relationships.

- Find models around the child of children who manage multiple families e.g. in friends’ families, on television, in books.

- Help the child think about/talk about the inevitability of mixed feelings.

- Watch for possible pressure points e.g. Mother’s Day, Father’s Day, Christmas, and find ways of indicating (where appropriate) that it is OK to give cards to more than one parent or to choose one rather than the other at different times.

- If necessary and with the child’s permission talk to the teacher about family issues that may disturb the child if raised in class, i.e. help others outside immediate family circle be aware of the child’s task in managing their multiple loyalties/families.

(Source: Providing a Secure Base, Gillian Schofield and Mary Beek, University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK)

Allowing children to take risks

As well as promoting the safety and welfare of children in their care, foster parents have to support and encourage children to take appropriate risks as part of normal growing up and to learn from their mistakes. This includes allowing children to participate in every day rough and tumble activities and physical sports, as well as permitting them the opportunities to participate in organised activities through school, such as outward bound weeks, canoeing and kayaking etc.

Decisions about what is an ‘appropriate risk’ will often be child specific and will relate to the child or young person’s previous experiences, age, developmental stage, confidence and other attributes. Foster parents should consult about and review such matters regularly with their supervising social worker and ensure that they are reflected in the placement plan. The principle is that children and young people in foster care should have the same opportunities as other children to try out new activities, take risks and learn from them. Foster parents should feel supported in helping children to do this and not feel that they cannot agree to anything.

Discipline and Sanctions

Disciplining children to develop an awareness of danger and respect for the rights, needs and feelings of others, as well as helping them to develop appropriate self-control, is a daunting responsibility for all parents and caregivers. Most parents use the experiences of their own childhood and family life as a basis for their approach to discipline.

Secure base theory and research into foster care tells us that foster parents need to be sensitive and try to identify and understand patterns of thinking and behaviour that reflect a child’s coping or defensive strategies. The focus should always be on helping the child to express and talk about their feelings and the foster parent must have the capacity to ‘stand in the shoes of the child’, before approaches to discipline are routinely adopted. This caregiving cycle begins with the child’s needs and behaviour but then focuses on what is going on in the mind of the caregiver. How a foster parent thinks and feels about a child’s needs and behaviour will determine his or her caregiving behaviours. The foster parent may draw on their own ideas about what children need or what makes a good parent from their own experiences or from what they have learned from training. The caregiving behaviours that result convey certain messages to the child. The child’s thinking and feeling about themselves and other people will be affected by these messages and there will be a consequent impact on his or her development. This process is represented in a circular model, the caregiving cycle, which shows the inter-connectedness of caregiver/child relationships, minds and behaviour, as well as their ongoing movement and change.

There is also a level of prescription about use of discipline and sanctions for fostered children and foster parents need to be aware of what the expectations are upon them.

Research indicates that looked after children on average are involved earlier and more often than other young people with the police and criminal justice system. Fosterplus is committed to trying to minimise the need for police involvement in dealing with challenging behaviour, and we wish to avoid criminalising foster children unnecessarily. You can contact your supervising social worker and/or our out of office hours service to discuss any concerns or issues that you may have concerning a young person’s behaviour.

Acceptable sanctions and punishments

Wherever possible, foster parents should use constructive dialogue with the child or guide them away from a confrontational situation. The aim at all times is to try to think flexibly about what the child may be thinking and feeling and to reflect this back appropriately to the child.

Foster parents should also have an understanding of their own emotional response to a confrontation or threat, and know when to withdraw, concede or seek help. Where sanctions are used, it is important that they are:

- Relevant for the child and related to his or her care plan, age and circumstances.

- Realistic and sensitive.

- Understandable for everyone in the household.

- Used sparingly.

- Time limited.

- Justified.

- Follow the behaviour as quickly as possible.

- Follow good practice in the care of children/young people.

- Have been discussed during the placement planning meeting.

- Recorded by the foster parents on the child’s CHARMS case record.

Sanctions/punishments may include:

- Loss of/withdrawing privileges – e.g. loss of staying up late on a special night of the week, or visiting friends. This can help the young person understand that the unwanted behaviour will not be tolerated.

- Going to bed early – This can be used alongside other methods of control, and is particularly useful when it is linked to behaviour in which the young person has been late home, been disruptive at bedtime etc. Young people should not be sent to bed more than one hour before their normal bedtime.

- Paying towards damages – Young people could be expected to pay a portion of their pocket money regularly until they have made amends, or made an agreed contribution towards damage. The whole of a child’s pocket money must never be taken. They must always have some money that is their own each week. Any money stopped for reparation is clearly recorded by the foster parent in their diary sheets and should have prior agreement of the child’s supervising social worker and local authority social worker.

- Doing extra jobs – Like tidying the living room each day for a week if they have been responsible for creating a messy environment for others.

- Grounding for a time – This should be used sparingly and linked to the behaviour which has been unacceptable e.g. the young person may have damaged trust by not returning home at the agreed time.

- No television or treat – A difficult punishment if it means that others in the family will also lose out, but possible to achieve if a young person has a particularly favourite programme, and it is possible to use another room while others watch TV.

- Withdrawing attention – This can be an effective means of decreasing unwanted behaviour in children by not giving any attention to the unwanted behaviour. Care should be taken to ensure that this behaviour would not result in the child being placed in any danger. Foster parents should also try to ensure that they do reward positive behaviour. Withdrawing attention should be for short impact periods only. A strategy could be to tell the child that if they sit quietly for ten minutes, then it will be time for a game.

- Time out – This gives everyone the opportunity to reflect on what has happened. Time out should only be used for very short periods, particularly if the child is young. Telling them to sit on a chair just outside the room that the foster parent is in for five minutes can constitute time out. Bedrooms where children have toys should not be used for time out.

- Verbal disapproval – A raised voice, or different tone, can signal to a child that the adult is displeased. Foster parents need to make clear to the child that it is the behaviour that is disliked, not the child. Children should not be reprimanded in public if possible.

- Increased supervision – Young people like freedom, and knowing that someone is taking a keener interest in their activities can help them re-consider how they behave.

- Contracts – These can be particularly useful for older children, or where a young person wants to work towards something. Contracts are a sophisticated measure which must be discussed with the Supervising social worker in the first instance.

Unacceptable measures of control and discipline

Unacceptable sanctions include those that intentionally or unintentionally humiliate a child or young person, cause them to be ridiculed, or have been experienced by a child or young person under different circumstances at home, and which may evoke past painful and traumatic memories.

Foster parents should never threaten to end a placement as a punishment for the child who is living with them. They may have previously experienced this threat being carried out in their own family, and it can seriously damage relationships in the foster home.

There are a number of unacceptable methods of control that are forbidden by legislation. These include:

- Corporal punishment – any intentional application of force as punishment, including smacking, slapping, punching, rough handling, grabbing and throwing missiles.

- Deprivation of food and drink.

- Restriction on visits to or communication with parents, relatives, social worker, children’s guardian, solicitor.

- Any requirement that a child wears distinctive or inappropriate clothes.

- Use or withholding of medication or dental treatment.

- Locking a child in a room or building. (This does not include time out in a child’s unlocked bedroom, the use of which should be limited and used in a positive way).

- Intentionally depriving the child of sleep.

- Imposing fines other than for compensation or repayment.

- Intimate physical examination of a child.

There are other unacceptable methods of control which are not forbidden by legislation, but which we would not accept as good practice, including:

- Keeping a child in isolation because of their behaviour – if isolation is necessary because of other reasons, it must only be with close adult supervision.

- Excessive use of sending a child to bed early as a punishment – bedtime should be a pleasant experience, and a child’s day should not end in an unsatisfactory way.

- Bribery or threats – this should not be confused with encouragement and praise as an incentive to promote appropriate behaviour.

Physical intervention by foster parents

Physical intervention on children should only be used in exceptional circumstances, where it is the only appropriate means to prevent likely injury to the child or other people, or likely serious damage to property.

In the event of a serious incident (e.g. accident, violence or assault, damage to property), foster parents should take what actions they deem to be necessary to protect children and themselves from immediate harm or injury. They must notify the agency immediately afterwards.

If there is a risk of serious injury, harm or damage to property, foster parents should not use any form of physical intervention, except as a last resort to prevent themselves or others from being injured, or to prevent serious damage to property. If any form of physical intervention is used, it must be the least intrusive necessary to protect the child, foster parent(s) or others. At no time should foster parents act unless they are confident of managing the situation safely, without escalation or further injury.

The agency will endeavour to deal with as many as possible of the challenges that are involved in caring for children without recourse to the Police, who should only be involved in two circumstances:

- An emergency necessitating their immediate involvement to protect the child or others; or

- Following discussion with the supervising social worker, Service Manager, Head of Operations, or the Out of Hours Manager (outside office hours).

If any serious incident occurs or the Police are called, the supervising social worker, Service Manager, Head of operations or Out of Hours must be notified without delay. They will then notify the relevant social worker(s) and arrange for a full report to be made of the incident and the actions taken.

Where there is significant evidence of patterns of violent or dangerous behaviours, the supervising social worker will liaise closely with the child’s social worker and foster parent, in order to agree how such behaviours should be best managed.

Recording of sanctions

Foster parents should record, in detail, any sanctions that they have used with a child or young person, including why they were used, what led up to the incident, an account of the behaviour/incident, and the consequences/outcome of the incident. Any triggers to the situation for the child/young person should be noted.

The information should be recorded on the carer log. Please inform your local office as soon as possible, by telephone, of any incident that you have recorded in CHARMS.

Where foster parents have used sanctions that were not previously agreed, it is particularly important that they carefully record the events and the sanctions used for discussion later with their supervising social worker, the young person, and where appropriate, their parent. The appropriateness of the actions should be discussed, and alternative action explored for the future if necessary.

The use of sanctions should be monitored for their effectiveness by the foster parent and supervising social worker. Significant use of an inappropriate sanction, or continued use of inappropriate sanctions may be deemed as a child protection issue and be investigated accordingly.

Suicide and self-harm

Looked after children are at greater risk of committing suicide than other young people. We must treat all histories and incidences of suicidal thoughts, suicidal attempts and self-harm seriously and not be tempted to deny or minimise their significance. We must not allow ourselves to be over optimistic about a child’s self-harming and assume that someone with a history of self-harming will not also attempt suicide. We must also be alert to recognising less common forms of self-harm such as refusal to take prescribed medication such as insulin. Dealing with a child who self-harms can be very frustrating, anxiety provoking and stressful. The trauma of the child can be transferred to the professional, who may react in a number of unhelpful ways, including intervention paralysis, drift or overreaction.

An intervention plan must be agreed with the local authority and foster parents must not act without the agreement and full knowledge of their supervising social worker. This area is one where individual, subjective thresholds play a very significant part in deciding whether we are concerned enough to intervene. The facts, history and risks must be established first, before decisions are reached about whether intervention or non-intervention is appropriate. Where there are differences in personal thresholds amongst professionals, we must work for consensus. When this cannot be achieved, we must establish and record clear accountability and decision making.

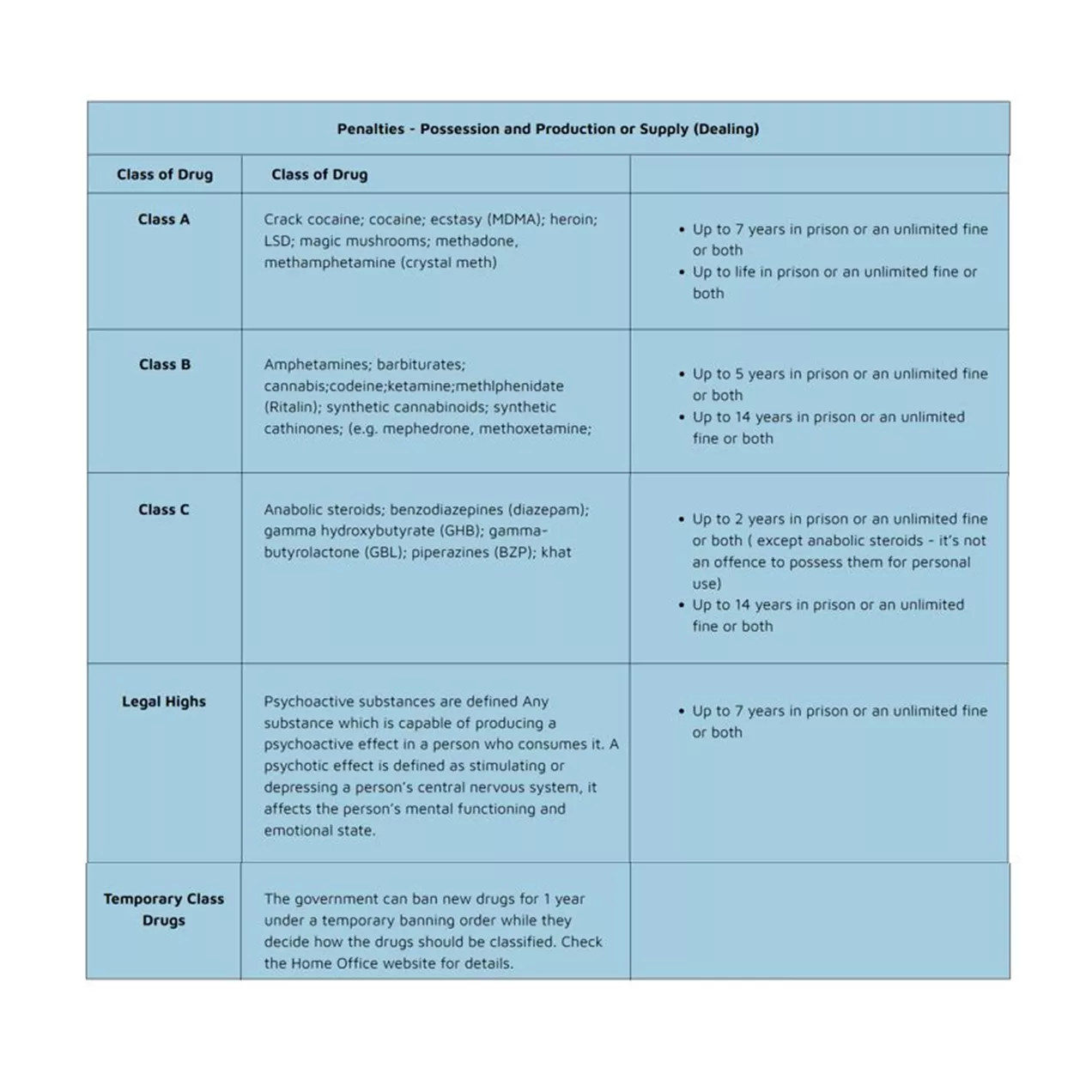

Confiscation of dangerous, illegal or unacceptable items

Any alcohol, illegal drugs, substances, solvents or weapons found in the possession of any child or young person should be confiscated by the foster parent and reported to, and handed in to, the child’s social worker or supervising social worker. Possession of such items should be considered as a significant incident and reported immediately to the supervising social worker or out of hours service. Fosterplus may seek advice regarding legal issues to assist everyone in determining the right way forward.

If foster parents discover that a child or young person in their care has taken illegal drugs, they must immediately contact their supervising social worker, or use the out of hours telephone support number to seek advice and action. It is not appropriate for foster parents to try and deal with this situation on their own.

Safeguarding Children / Child Protection

What is child abuse?

It is generally accepted that there are four main forms of abuse. The following definitions are taken from National Guidance for Child Protection in Scotland 2014

Physical Abuse

Physical abuse is the causing of physical harm to a child or young person. Physical abuse may involve hitting, shaking, throwing, poisoning, burning or scalding, drowning or suffocating. Physical harm may also be caused when a parent or carer feigns the symptoms of, or deliberately causes, ill health to a child they are looking after. For further information, see the section on Fabricated or induced illness.

Emotional abuse

Emotional abuse is persistent emotional neglect or ill treatment that has severe and persistent adverse effects on a child’s emotional development. It may involve conveying to a child that they are worthless or unloved, inadequate or valued only insofar as they meet the needs of another person. It may involve the imposition of age – or developmentally – inappropriate expectations on a child. It may involve causing children to feel frightened or in danger, or exploiting or corrupting children. Some level of emotional abuse is present in all types of ill treatment of a child; it can also occur independently of other forms of abuse.

Neglect

Neglect is the persistent failure to meet a child’s basic physical and/or psychological needs, likely to result in the serious impairment of the child’s health or development. It may involve a parent or carer failing to provide adequate food, shelter and clothing, to protect a child from physical harm or danger, or to ensure access to appropriate medical care or treatment. It may also include neglect of, or failure to respond to, a child’s basic emotional needs. Neglect may also result in the child being diagnosed as suffering from “non-organic failure to thrive‟, where they have significantly failed to reach normal weight and growth or development milestones and where physical and genetic reasons have been medically eliminated. In its extreme form children can be at serious risk from the effects of malnutrition, lack of nurturing and stimulation. This can lead to serious long-term effects such as greater susceptibility to serious childhood illnesses and reduction in potential stature. With young children in particular, the consequences may be life-threatening within a relatively short period of time.

Sexual abuse

Sexual abuse is any act that involves the child in any activity for the sexual gratification of another person, whether or not it is claimed that the child either consented or assented. Sexual abuse involves forcing or enticing a child to take part in sexual activities, whether or not the child is aware of what is happening. The activities may involve physical contact, including penetrative or non-penetrative acts. They may include non-contact activities, such as involving children in looking at, or in the production of indecent images or in watching sexual activities, using sexual language towards a child or encouraging children to behave in sexually inappropriate ways (see also section on child sexual exploitation).

Peer on Peer Abuse

The term ‘peer on peer abuse’ relates to various forms of abuse, where all parties involved are under the age of 18 years. The abuse can include violence and criminal activity, harmful sexual behaviour, sexual exploitation, relationship abuse and bullying (including cyberbullying) and is harmful to both the victim and the perpetrator due to their status as children.

The victims of peer on peer abuse are both male and female and particularly vulnerable groups include those with disabilities and those who represent minority groups (e.g. on basis of sexuality, race or religion). Peer on peer abuse is often a feature of gang activity, and a victim might experience a combination of different abuses and have multiple support needs.

Where does peer on peer abuse occur?

Young people in foster care might experience abuse from their peers:

- Within the foster home

- At school

- At clubs/social activities

- On public transport/walking to school

Agency response

Foster parents and agency staff need to be alert to the signs of peer on peer abuse and be familiar with agency policies to ensure a swift and appropriate response. Young people’s risk assessments should identify key concerns and safeguarding measures both for use within the home and community.

- Being aware of, and managing bulling:

Bullying is defined as “behaviour by an individual or group, usually repeated over time, which intentionally hurts another individual or group either physically or emotionally.” Bullying behaviour can include name calling, hitting, pushing, spreading hurtful and untruthful rumours, taking belongings, inappropriate touching or excluding someone from a social group. Young people might be targeted as a result of their race, religion, sexuality or disability and bullying might take place online. This is known as ‘cyberbullying’. The Anti-Bullying Alliance has an excellent interactive online resource for parents and foster parents to raise awareness of bullying issues, https://anti-bullyingalliance.org.uk

- Gangs awareness

Young people can be exploited physically and/or sexually by a gang or group of young people. Gangs (mainly comprising young men and boys aged 13-25 years) are typically involved in various forms of criminal activity including violence with knives and guns, robbery and intimidation, exposing both gang members and targets to harm. Gangs are characterised by their identifiable markers including territory, name and clothing, while other groups without specific gang characteristics exist within the community and online to exploit young people, often sexually.

Click here to view a helpful Government guide to gang activity for parents and carers >

- CSE awareness

The sexual exploitation of young people by adult perpetrators has been well publicised with recent prosecutions of adult males in Rotherham and Rochdale. Young people can also be sexually exploited by older young people and this is reflected in the most recent definition:

CSE “occurs when an individual or group takes advantage of an imbalance of power to coerce, manipulate or deceive a child or young person under the age of 18 into sexual activity”

CSE always involves in imbalance of power and victims might not be aware of the exploitation, perceiving the relationship as loving. https://www.kscmp.org.uk/guidance/exploitation

- Youth produced sexual imagery (“sexting”)

The sharing of nude images online between young people is not always intentionally harmful but has the potential to harm if there are elements of coercion, bribery and/or blackmail involved. Young people can feel pressured to send nude images and once images have been shared they lose control over them; the image can be copied and shared indefinitely. The law prohibits the taking, possessing and sharing of ‘indecent images of children’ which includes nude images shared between young people, if the subject of the image is under 18 years of age. Young people who are involved in this behaviour can therefore need support with both the emotional impact of image sharing as well as possible police investigations.

CEOP has a helpful online guide for parents and carers >

Resources for young people

Childline: 0800 11 11 or find out about the “For Me” app at https://www.childline.org.uk/toolbox/for-me/

National Guidance for Child Protection in Scotland 2014

The Scottish Government’s guidance on inter-agency working to safeguard and promote the welfare of children can be downloaded at:

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/working-together-to-safeguard-children–2

Staff and foster parents who are in positions of trust

Legislation states that it is a criminal offence for adults who are in positions of trust to commit sexual acts (including inappropriate touching), or have sexual relationships, with young people between the ages of 16 to 18 years in their care (even if the young person initiates or consents to the sexual activity). This legislation also applies to people over the age of 18 years if they are deemed to be ‘vulnerable’. The legislation is primarily intended to protect young people where a relationship of trust with an adult looking after them exists.

A position of trust can be broadly defined as a relationship in which one party is in a position of power or influence over the other by virtue of their work or nature of their activity. A young person is vulnerable to exploitative contact or relationships irrespective of their chronological age. Some work roles such as Social Worker or foster parent are defined within the legislation as being positions of trust. Positions of trust may also be created by virtue of the nature of the adult’s contact with a young person; for example a relative of a foster parent caring for a fostered child for short periods during the daytime would be in a position of trust. Adult members of the foster parent’s household including sons and daughters may also be seen to hold positions of trust in some circumstances.

Allegations or complaints would be subject to the procedures defined in the Scottish Government guidance Managing Allegations against foster parents and approved Kinship Carers (2013). Fosterplus’s Child Protection procedures take account of this guidance. Conviction of criminal charges under this legislation may lead to a custodial sentence and a referral to the Disclosure and Barring Service.

If a foster parents feels sexually attracted to a young person they care for, they have a personal and professional responsibility to inform their supervising social worker. The social worker must consult with their Registered Manager and the Quality Assurance and Safeguarding Team as to the appropriate actions to safeguard the young person concerned (including moving the young person to a different placement).

Disclosure Scotland Checks

Applicants to foster and all people aged 16 or over living or regularly visiting their household will be asked to complete the disclosure forms and produce the necessary identification. There are different levels of checks the highest being PVG (Protecting Vulnerable Groups) and depending on the role of the individual different checks will apply. These will then be sent to the Disclosure Scotland Service by the fostering service. Disclosure Scotland checks are not transferable, so copies of checks carried out by other agencies or for other posts cannot be accepted. Checks will be updated at least every three years.

Child Sexual Exploitation (CSE)

Child sexual exploitation takes different forms – from a seemingly ‘consensual’ relationship where sex is exchanged for attention, affection, accommodation or gifts, to serious organised crime and child trafficking. Child sexual exploitation involves differing degrees of abusive activities, including coercion, intimidation or enticement, unwanted pressure from peers to have sex, sexual bullying (including cyber bullying), and grooming for sexual activity. Child sexual exploitation is not gender specific. There is increasing concern about the role of technology in sexual abuse, including via social networking and other internet sites and mobile phones. The key issue in relation to child sexual exploitation is the imbalance of power within the ‘relationship’. The perpetrator always has power over the victim, increasing the dependence of the victim as the exploitative relationship develops.

Many children and young people are groomed into sexually exploitative relationships but other forms of entry exist. Some young people are engaged in informal economies that incorporate the exchange of sex for rewards such as drugs, alcohol, money or gifts. Others exchange sex for accommodation or money as a result of homelessness and experiences of poverty. Some young people have been bullied and threatened into sexual activities by peers or gangs which is then used against them as a form of extortion and to keep them compliant.

Children and young people may have already been sexually exploited before they are referred to children’s social care; others may become targets of perpetrators whilst living at home or during placements. They are often the focus of perpetrators of sexual abuse due to their vulnerability. All staff and foster parents should therefore create an environment which educates children and young people about child sexual exploitation, involving relevant outside agencies where appropriate. They should encourage them to discuss any such concerns with them, another member of staff, or with someone from a specialist child sexual exploitation project, and also feel able to share any such concerns about their friends.

As an agency, Fosterplus has a strong commitment to learning and development and believes that this is an important part of exploring the subject of Child Sexual Exploitation. Core training has been specifically designed by the agency and all foster parents, staff, panel members and volunteers are expected to attend this course which explores the meaning of Child Sexual Exploitation and working with children who have been or are at risk of being sexually exploited.

Child Sexual Exploitation Risk Assessments

These assessments are completed in addition to ‘Safeguarding Risk Assessments’ where there is an indication or concern that the child or young person is at risk of Child Sexual Exploitation (CSE). The CSE Risk Assessment provides a method of establishing the level of risk the young person is at of being a subject of Child Sexual Exploitation. This risk assessment focuses specifically on the known vulnerabilities and indicators of Child Sexual Exploitation. However, these assessments must be considered alongside regular Safeguarding assessments as each should inform the other.

Female Genital Mutilation

Female genital mutilation (FGM) is a collective term for procedures which include the removal of part or all of the external female genitalia for cultural or other non-therapeutic reasons. The practice is medically unnecessary, extremely painful and has serious health consequences, both at the time when the mutilation is carried out and in later life. The procedure is typically performed on girls aged between 4 and 13, but in some cases it is performed on new-born infants or on young women before marriage or pregnancy.

FGM has been a criminal offence in the U.K. since the Prohibition of Female Circumcision Act 1985 was passed. The Female Genital Mutilation Act 2003 replaced the 1985 Act and made it an offence for the first time for UK nationals, permanent or habitual UK residents to carry out FGM abroad, or to aid, abet, counsel or procure the carrying out of FGM abroad, even in countries where the practice is legal.

The rights of women and girls are enshrined by various universal and regional documents which highlight the right for girls and women to live free from gender discrimination, free from torture, to live in dignity and with bodily integrity.

Where a foster parent has concerns about the welfare and safety of a child or young person in relation to Female Genital Mutilation they should immediately inform their supervising social worker.

Trafficked Children

Who are trafficked children?

Trafficked children are likely to be children who arrive in the country as unaccompanied children or asylum seekers. They are brought into the country for the purposes of adult exploitation, which could include prostitution or sexual abuse, forced or/and cheap labour, slavery or servitude, financial or benefits fraud, and being used as drug ‘mules’. Such children may be unaware that they have been brought into the country for such purposes, others may be too frightened to tell, whilst a few may be aware but compliant.

Identifying trafficked children

Unaccompanied children arriving in the country are screened by the immigration authorities at the point of entry. Some children will have only vague arrangements as to their future care or the immigration authorities may have concerns about the adults who have been identified as their future foster parents. Such children are likely to be placed with foster parents for at least a short period pending the outcome of further investigations. These children are at particular risk of adult exploitation, but will rarely disclose their experiences directly to a foster parent. However, children are likely to show patterns of behaviour and activity which may indicate that the child is the subject of adult exploitation. These include:

- Does not appear to have any money but does have a mobile phone when first placed.

- Receives unidentified/unexplained phone calls.

- Possesses money/goods not accounted for.

- Has a prepared story and appears to have been coached or rehearsed in recounting how they arrived in the country.

- Shows signs of physical or sexual abuse or sexually transmitted disease or pregnancy.

- Has unexplained absences from the foster parents’ home or goes missing.

- Unidentified adults loitering outside or near foster parents’ home.

- Has significant sums of money which are not adequately accounted for.

- Acquires expensive clothes, mobile phones etc. without plausible explanation.

- Possesses keys to unidentified premises.

- Truancy.

- Observed entering or leaving cars driven by unknown adults.

- Found in areas the child has no known links with.

- Inappropriate use of internet and forming online relationships with adults.

These indicators are not a definitive list but provide a guide to alert foster parents that a child might be ‘trafficked’.

Safeguarding children at risk of being trafficked

When unaccompanied children are first placed with foster parents, the local authority should undertake a risk assessment of the child and should plan for the possibility that the child may be ‘trafficked’. If and when a foster parent feels that there is evidence that the child may be ‘trafficked’, then they should report their concerns to their supervising social worker who will liaise with the local authority social worker. The local authority will decide whether the concerns or evidences warrant the implementation of formal child protection procedures.

Children Missing from Care

Children at risk of going missing

At the point a child is placed with foster parents there should be a Risk Assessment completed, which will include any specific factors that may increase the possibility of the child going missing. Any identified risk factors should then be addressed in a way that will reduce the possibility of a child going missing. For example, clear arrangements for contact between a foster child and his/her birth family may decrease a child’s level of anxiety about seeing his/her family and therefore their likelihood of running away.

In addition to the Risk Assessment, the foster parent and/or supervising social worker should complete a record detailing information such as the child’s height, distinguishing features etc. which can be given to the Police if the child is actually reported as missing. This may include a photo, which should only be taken with the child’s agreement and those who hold parental authority.

The placement plan should define the circumstances in which a child is authorised to be absent from a foster parent’s home. For example, it could record that an older teenager may stay with a close friend one night every two weeks on an on-going basis, without identifying the specific dates. The placement plan should detail who has authority to agree such an arrangement on each individual occasion e.g. the foster parent, and whether the foster parent should inform each absence to the Fosterplus OOH service. These arrangements would be viewed as authorised absences rather than unauthorised absences or a missing child.

Foster parents should know when to try to prevent a child or young person leaving the home and should do so through dialogue, but they should not physically intervene to try to restrain any child should they be intent on leaving, or in any other circumstances, unless it is necessary to prevent injury to the child or others, or serious damage to property. No physical intervention may be excessive or unreasonable.

What to do when a child or young person is missing

In order to avoid any confusion, Fosterplus foster parents should, in all instances where a child is absent from their care without permission, contact their supervising social worker or their Service Manager during normal working hours, or the OOH service at evenings or weekends, to report the child’s absence.