Foster Parent Handbook

Chapter 5

Colour Code Key:

Fosterplus Policies, Procedures and Guidance

Legislation and Government Guidance

General Sources and Good Practice Information

The Framework for Care Planning

Wellbeing

Wellbeing sits at the heart of the GIRFEC approach and reflects the need to tailor the support and help that children, young people and their parents are offered to support their wellbeing.

A child or young person’s wellbeing is influenced by everything around them and the different experiences and needs they have at different times in their lives.

Eight indicators of wellbeing or as they are often referred to SHANARRI

- Safe

Protected from abuse, neglect or harm at home, at school and in the community. - Healthy

Having the highest attainable standards of physical and mental health, access to suitable healthcare and support in learning to make healthy, safe choices. - Achieving

Being supported and guided in learning and in the development of skills, confidence and self-esteem, at home, in school and in the community. - Nurtured

Having a nurturing place to live in a family setting, with additional help if needed, or, where possible, in a suitable care setting. - Active

Having opportunities to take part in activities such as play, recreation and sport, which contribute to healthy growth and development, at home, in school and in the community. - Respected

Having the opportunity, along with foster parents, to be heard and involved in decisions that affect them. - Responsible

Having opportunities and encouragement to play active and responsible roles at home, in school and in the community, and where necessary, having appropriate guidance and supervision, and being involved in decisions that affect them. - Included

Having help to overcome social, educational, physical and economic inequalities, and being accepted as part of the community in which they live and learn.

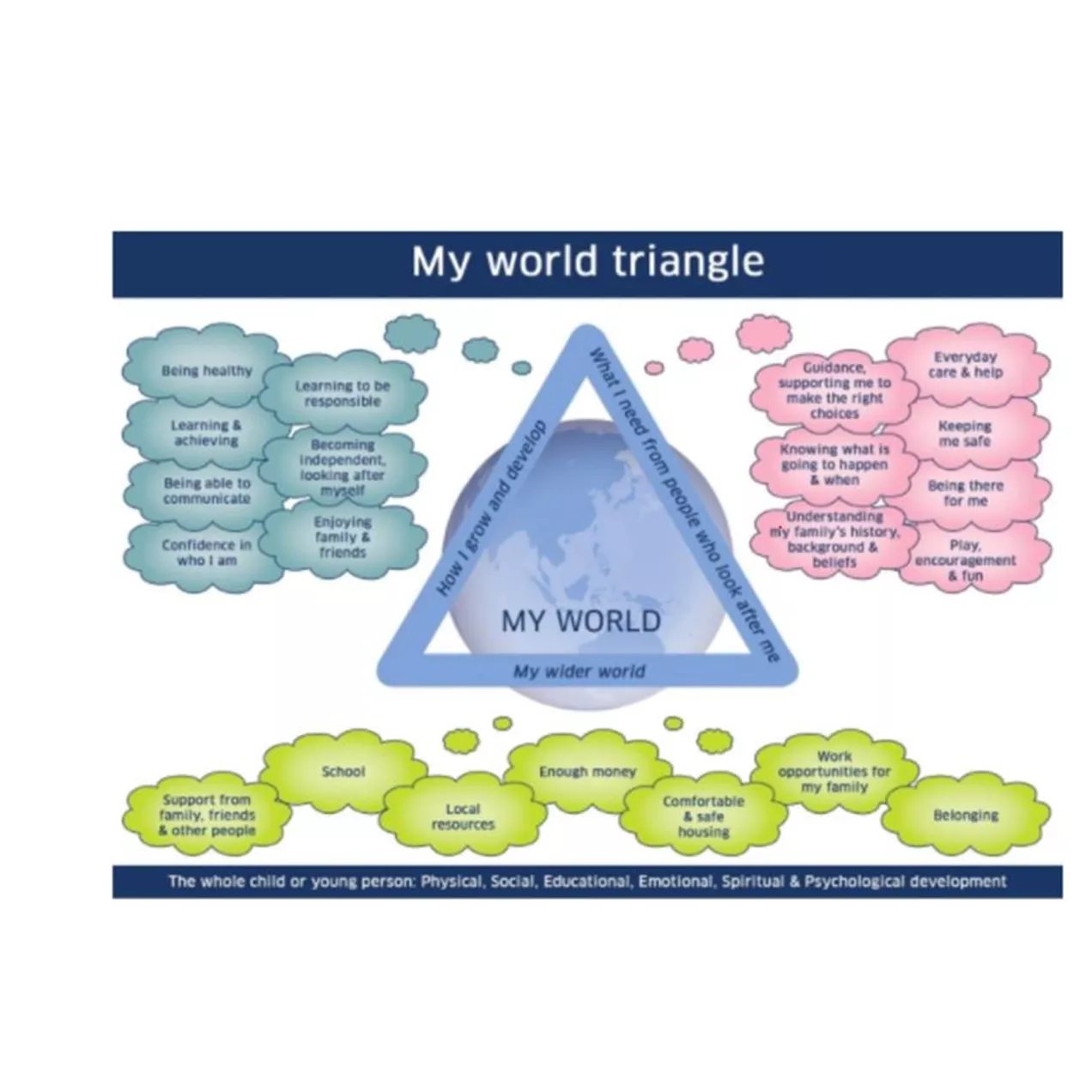

My world triangle is used to think about the whole child world of the child or young person and can be helpful to gather information from other sources to identify the strengths or wellbeing concerns of the child or young person’s world.

Contents of a Care Plan

What is a care plan?

Every child that is looked after has a care plan. It should contain information about how the child’s developmental needs – for example, in relation to health and education – will be met, as well as the arrangements for their current and longer term care. It should provide clarity about the allocation of responsibilities and tasks, in the context of shared parenting between parents, the child’s foster parents and the corporate parents (i.e. the responsible local authority).

What’s in a Child’s Plan?

Every plan, should include and record:

- information about the child’s wellbeing needs including the views of the child and their parent(s);

- details of the action to be taken;

- the service(s) that will provide the support;

- the way in which the support is to be provided;

- the outcome that the plan aims to achieve; and when the plan should be reviewed.

- A Child’s Plan will also record who will coordinate the support. This person is known as the Lead Professional for the plan who will work with the child and their parent(s) to keep them informed.

Timeframe for drawing up a care plan

The Looked After Children (Scotland) Regulations 2009 state that whenever practicable, the plan for the immediate arrangements for the child should be drawn up before the placement is made. Otherwise it should be drawn up as soon as practicable after the child is placed. It should be reviewed, and where necessary adjusted, at the first and at subsequent reviews and/or if the child changes placement. The initial plan will primarily address the immediate arrangements to meet the child’s care needs. It may require further assessment within a time limited period, defined in local authority procedures and monitored through reviews, to complete a comprehensive assessment. This may then raise more detailed and specific matters which have to be addressed to meet the child’s longer term needs.

Contents of a care plan

It is important that the care plan records information which will help the child, parent/s and foster parent/s understand why decisions have been or are being made. Although each local authority has its own format for the paperwork, there are specific requirements regarding the preparation of a care plan and its contents. It is best to think of the care plan as a range of information and plans about a child or young person that together go to make up the overall care plan.

The first LAAC review, which considers whether the care plan, should take place within six weeks of the placement and then at three months and thereafter no less frequently than 6 monthly. A number of local authorities may hold reviews at shorter intervals in the early stages of looking after children, especially where they are planning for young children with an intensive intervention or support programme, to establish if return home is feasible, and if so, followed by active planning for stability and permanence for the children.

The review should assess:

- the child’s needs and how those needs are being met;

- the child’s long term needs and how those needs are being or can be met;

- whether the child’s welfare is being safeguarded and promoted;

- the child’s development;

- whether the accommodation is suitable for the child; and

- the child’s educational needs and whether those needs are being met.

The child’s plan will be revised to take account of the outcome of the review.

The care plan should record the views of the child and other relevant people about the arrangements for the child. The purpose of an LAAC review is to monitor and update the child’s care plan – it will be the responsibility of the child’s social worker to update the child/young person’s assessed needs prior to every case review.

Looked After Regulations

The duties of local authorities towards looked after children in relation to care planning are laid out in the Looked After Children (Scotland) Regulations 2009 which can be downloaded from:

Staying Put and Continuing Care

A ‘Staying Put’ Approach will enable young people to enjoy a transition from care to adulthood that more resembles that which is experienced by their non-looked after peers.

STAYING PUT SCOTLAND https://www.gov.scot/publications/staying-put-scotland-providing-care-leavers-connectness-belonging/

The aim of Continuing Care, a term introduced by the Children and young Person (Scotland) Act 2014, is to provide young people with a more graduated transition out of care, reducing the risk of multiple simultaneous disruptions occurring in their lives while maintaining supportive relationships.

Local authorities have a statutory duty to prepare young people for when they leave care, and to provide guidance and assistance for young people who have ceased to be looked after over school age up to eighteen, and a power to do so up to twenty six. Section 66 of the Children and Young People (Scotland) Act 2014 provides young care leavers with the right to request advice, guidance and assistance from the local authority up to twenty six years of age. In response to this request, the local authority will then be under a duty to conduct an assessment of the needs of that care leaver. If the care leaver has “eligible needs‟ then the local authority must ensure that support is provided to meet those needs.

The Child’s Social Worker and Local Authority Responsibilities

What are the responsibilities of the child’s social worker?

Each looked after child is allocated a social worker by the responsible local authority. The duties of the child’s social worker include:

Preparation of the care plan

It is the role of the child’s social worker to ensure that adequate arrangements are made for the child’s care and that a care plan is made, in partnership with the child, their foster parent/s, their parents and other agencies.

Implementation and review of the care plan

The social worker is also responsible for ensuring that the care plan is implemented and reviewed, although many of the actions may be the responsibility of other agencies.

Monitoring the child’s welfare

The child’s social worker must exercise professional judgement, based on a good enough knowledge of the child and the foster parent/s, about whether the child’s welfare is being adequately safeguarded. As children cannot always describe their feelings, the social worker needs to gain an understanding of what the child’s daily life and routines in the placement are like. A child may also speak more freely if they can spend time with the social worker outside the placement.

Advice, support and assistance for the child

In between visits, the child’s social worker must ensure that advice, support and assistance are available to the child, and that, appropriate to the child’s age and understanding, s/he knows how to seek this. This will include information about the authority’s comments and complaints procedures and how to access advocacy.

Advice and assistance to the foster parent/s

It is also part of the child’s social worker’s role to offer advice and assistance to the foster parent/s. With an independent agency like Fosterplus, this should involve close working with the supervising social worker to ensure that there is not a duplication of efforts.

How often should the child’s social worker visit?

The frequency of visits to looked after children is laid down in the looked after regulations. Remember, these are visits to the foster home in addition to any that the supervising social worker may make.

The child should be visited within one week of the start of any placement by their social worker, or someone designated by the local authority. After that, they must be visited at intervals of not less than three months from the date of the previous visit.

LOCAL AUTHORITY DUTY TO VISIT

The local authority must ensure that the child and their foster parent are visited on their behalf–

(a) within one week of the placement being made; and

(b) thereafter at intervals of not more than 3 months from the date of the previous visit.

Looked After Children (Scotland) Regulations 2009 download from:

However, these are minimum visiting requirements and the frequency of visits will normally be determined by individual circumstances. A very young child or a child who has been abused may be anxious about spending time with a person they do not know well. A social worker may decide to visit a child more frequently when they first starts to be looked after or when first allocated to them, to allow a relationship to develop.

Early on in a placement, the child’s social worker should agree with the foster parent the frequency of visits and the times that are convenient for the foster family. Foster parents should be clear about their family needs and not allow visits to be scheduled at times that disrupt important routines.

The social worker should visit the child outside the statutory minimum intervals when reasonably requested to do so by the child or the child’s foster parent/s. There are some obvious circumstances where more frequent visits above the minimum will be necessary. For example, where the role of the child’s parents is changing, the child’s needs have changed, or during periods when the foster parent/s or the placement may be under particular stress. The LAAC review will often stipulate the frequency of visits expected.

The law is clear that visits should not be neglected because a placement is going well. The minimum requirements help to ensure the child’s social worker is equipped to identify and help with any difficulties, because care has been taken to establish a relationship with a child and foster parent.

It is viewed as good practice for children’s social workers to undertake joint visits with a supervising social worker to a foster home at least twice a year and more often where a placement appears unstable.

What should the child’s social worker do when they visit?

The child’s social worker represents the local authority responsible for the child and has a duty to make sure that the child or young person is being well looked after physically and emotionally. If the child’s social worker asks to see where the child sleeps, for example, foster parents should not feel that this demonstrates that they don’t trust them. Instead, it shows that the social worker is doing a thorough job, and takes their responsibilities towards the child seriously.

One of the social worker’s statutory responsibilities is to make time to see the child alone. The exceptions to this are:

- Where the child refuses (and is of sufficient age and understanding to refuse).

- Where the social worker considers it inappropriate to do so (having regard to the child’s age and understanding).

Foster parents can help by preparing the child for the visit and by allowing time and space for the child and the social worker to talk together. Some foster parents may feel that a separate interview and perhaps a trip out with the social worker emphasises the differences between fostered children and their own children. However, we all have to acknowledge that the position of a child in foster care is different – the child has a family with whom the social worker is a vital link and the child must be allowed to talk through any worries and concerns.

It is important, though, that foster parents do not feel that the child and social worker are secretly going to air grievances about the placement. The social worker should let the foster parent know what sorts of discussions take place with the child (without breaking confidences).

If a child has particular communication difficulties or requires specialist communication support, the child’s social worker is expected to use specialist resources in order to ensure that the child has the opportunity to express their wishes and feelings.

What should foster parents discuss with the child’s social worker?

The foster parent and the child’s social worker will have significant information to exchange about the child or young person at every visit. The social worker should keep foster parents up to date on any developments within the child’s family and any forthcoming legal proceedings. If changes to the placement plan are being considered, they should be discussed.

The child’s social worker will want to hear about the child’s day to day progress, and foster parents should keep a written record of this to jog their memory. The social worker will be particularly interested in the child’s reactions to contact with parents, progress at school, relationships with other children and with the foster parent and their family.

Foster parents spend far more time with the foster child than the social worker does and are more likely to receive confidences about the child’s state of mind, troubles at school and so on. Experienced foster parents will be able to judge when a confidence can be respected and when important information must be shared with the social worker. If in doubt, the social worker should be told and the reasons for this explained to the child. Foster parents can discuss this sort of thing with their supervising social worker.

The child’s or young person’s behaviour will probably be discussed at every visit. If foster parents are experiencing difficulty with the child’s behaviour, they should voice any concerns they have, and should not feel that they have failed by not being able to cope, nor that they are ‘telling tales’ behind the child’s back. The social worker needs to know, and the foster parent’s aim is to get the social worker to listen to what is being said.

Foster parents should keep a record of the child’s behaviour; they will then feel confident about explaining exactly what is going on to the social workers. It is the job (the expertise) of both the child’s social worker and the supervising social worker to recognise the feelings voiced by the foster parent/s, to consider what the child’s behaviour says about the child and what effect it is having on the foster parent/s and their family.

There will be situations where the social workers can make positive suggestions for change, but there will be others in which they may simply not know how best to advise the foster parent. The social workers should say so and seek further help. It may be that the child’s own parents can assist in interpreting difficult or puzzling behaviour. All those involved in foster care recognise that coping with behaviour problems within the foster home can be exhausting and traumatic. So in situations where foster parents are coping with difficult behaviour, it is particularly important that the social workers and the foster parent are able to communicate well.

Social workers are expected carefully to record the content and outcome of each visit to a looked after child. Information from the visit will be shared appropriately with parents and the child’s foster parents and others who may need to know. The child’s social worker should discuss with the child, subject to their age and understanding, what information should be shared with whom and why.

Role and Responsibilities of the Reviewing Officer

The regulations are clear about frequency of reviews, who to consult and the broad areas to address. They are not prescriptive about how they should be carried out. However, they are clear that chairing of the review is by someone who has no direct day-to-day responsibility for the case, to maintain the objectivity and accountability for the management of the case. This should be laid out in local authority procedures. A significant number of local authorities have independent reviewing officers (IRO) who ensure a well-run reviewing process and have contributed significantly to the development of this important area of work. The differing sizes, structures and geographical aspects of local authorities in Scotland mean that some variation in the exact provision for carrying out reviews is possible, as long as authorities can demonstrate that they meet the requirements and fulfil their functions. There may also be some variation within individual authorities if these contribute to the effectiveness of reviews.

There are two clear and separate aspects to the function of the Reviewing Officer

- Chairing the child’s LAAC review; and

- Monitoring the child’s case on an ongoing basis, including whether any safeguarding issues arise.

If a foster parent has concerns that care plans are not being progressed as agreed at a LAAC review, you should first discuss this with your supervising social worker to ensure that everything has already been tried to resolve this with the child’s social worker and manager/s.

Looked after Children Reviews

What is the purpose of the looked after and accommodated child’s case review?

The purpose of a LAAC review is to assess how far the care plan is addressing the child’s needs and whether any changes are required to achieve this. The focus of the first case review meeting will be on examining and confirming the plan. Subsequent case reviews will be occasions for monitoring progress against the plan and making decisions to amend the plan as necessary, to reflect new knowledge and changed circumstances.

Timing of case reviews

The minimum frequency for case reviews is:

- First Review – within 6 weeks of child becoming looked after

- Second Review – within three months of the first review

- Subsequent Reviews – not more than six months after any previous review

Reviews can take place more frequently than the minimum standard and should take place as often as the circumstances of a case require. Whenever there is a need for significant changes to the care plan these should be considered first at a case review, unless this is not reasonably practicable.

Child protection review conferences – timing in relation to LAAC review

Where a looked after child is also subject to a child protection plan, it is expected that there will be a single planning and reviewing process, led by the reviewing officer. The timing of a child protection review conference should be the same as the looked after child case review to ensure that information in relation to the child’s safety is considered within the case review meeting, and informs the overall care planning process.

Preparation for looked after and accommodated child review meetings

Meetings should always be held at a time and place that will be most likely to provide a setting and atmosphere conducive to the relaxed participation of those attending. Particular regard should be paid to the needs of the child and the child’s views about the venue should be sought. The timing should be appropriate to the child’s needs and avoid requiring the child to miss school or other commitments.

The child’s social worker must consult the foster parent/s first if it is proposed to hold a review meeting in the foster parent/s’ home.

The child’s social worker should consider the possibility of an advocate accompanying the child to the review meeting.

Subject to any agreed exclusions, the following people will normally be invited to a review meeting:

- The child.

- The parent/s and/or those with parental responsibility.

- The foster parent/s.

- The supervising social worker.

- A representative from the child’s school/the Education Service

- LAC nurse and/or health visitor.

Other people with a legitimate interest in the child should only be invited if they have a contribution to make to the case review meeting, including Health representatives. Where it is considered that written views or reports will be adequate, these should be sought and obtained in time to be considered as part of the case review meeting. The emphasis should always be to maintain a child-friendly meeting and numbers kept to a minimum.

Where a permanence plan is in place, a small group (those consistently and constantly involved with the child) will normally be identified as essential attendees at the next and subsequent case review meetings. In the majority of cases, the group will consist of the social worker, the child, parents, foster parents, supervising social worker and the reviewing officer. This will vary according to the circumstances of the individual case.

The child’s social worker must arrange for consultation papers to be sent out for the following participants:

- Child/young person.

- Foster parent/s.

- Parents/persons with parental responsibility (but not if the child is freed for adoption).

The foster parent/s may be asked to provide a written report for the case review meeting and should discuss this with their supervising social worker.

The LAAC meeting

The IRO will attend and chair the meeting, unless it is not practicable to do so.

The following are minimum requirements for matters to be considered at any case review:

- The effect of any change in the child’s circumstances since the last case review.

- Whether decisions taken at the last case review have been successfully implemented, and if not the reasons for that.

- Whether there is a plan for permanence.

- The current arrangements for contact and whether there is a need to change these arrangements to promote contact between the child and their family or other relevant people.

- Whether the placement continues to be appropriate and is meeting the needs of the child.

- The child’s educational needs.

- The child’s leisure interests and activities and whether the current arrangements are meeting the child’s needs.

- The child’s health needs.

- Whether the identity needs of the child are being met and whether any changes are needed, having regard to the child’s religious persuasion, racial origin and cultural background.

- Whether the child understands any arrangements made to provide advice, support and assistance and whether these arrangements continue to meet their needs.

- The child’s wishes and feelings about their care plan including in relation to any changes or proposed changes to the care plan (having regard to their age and understanding).

- Whether the plan fulfils the responsible authority’s duty to safeguard and promote the child’s welfare.

- Whether there is a need to consider referring back to the Children’s Hearing system.

The reviewing officer must ensure that a named person is identified as having responsibility for the implementation of each decision made at the LAAC review, within an agreed timescale. The decisions should be framed in such a way that the identified needs and planned outcomes are clear. The person responsible for implementing the decision and the timescale for implementation must be recorded.

Where disagreements or differences in opinion arise in the course of the LAAC review process between those present, every effort should be made to resolve the matter on an informal basis. Where agreement cannot be reached, the child’s social worker should ensure that the child, parents, foster parents and others involved with the child are aware of the local authority’s complaints procedure.

The reviewing officer is under a duty to advise the child of their right to make a complaint and of the availability of an advocate to assist the child in making a complaint.

The report of the LAAC review meeting

The child’s social worker must ensure that copies of the report of the case review meeting are given to:

- The child (if appropriate).

- The child’s parents.

- Anyone with parental responsibility.

- Anyone else considered relevant, including the foster parent/s.

Minutes of the LAAC review

A record of the discussion and the decisions are minuted and distributed to the same group.

Placement Stability Planning

Fosterplus strongly believes that children and young people should not experience further trauma of a placement breakdown and is fully committed to providing additional support to placements that are at risk of breaking down.

The Agency has a strong Learning and Development Policy which explores how to help and support foster parents in managing challenging behaviour. The Agency is also dedicated to retaining qualified, experienced staff supervising a small number of foster parents in order that support can be readily available. There is also an Out Of Hours system to ensure that no foster parent feels alone, and without support.

It will always be the aim of Fosterplus that every effort will be made to prevent the disruption of a placement. We maintain a RAG (Red/Amber/Green) rating system on children’s CHARMS case records to flag placements that may be at risk and supervising social workers regularly review the placement stability plans with their managers. For all children or young people where there is an amber or red rating there should be an action plan agreed to address the issues being flagged. This should include the foster parent, the local authority social worker and the young person.

Where it appears that there may be a disruption, in the first instance additional support will be offered to address the issues of concern. This will be in the form of:

- Consultation and support for the child/young person, initially with their social worker and or the agency supervising social worker, to enable them to express their views or to consider how issues can possibly be resolved;

- Support for the foster parents from their supervising social worker and other professionals as required, to consider options where they could adapt their practice or how the child could be encouraged to adapt the behaviour that is likely to disrupt the placement;

- Additional learning and development opportunities to further develop skills;

- Ongoing monitoring of the issues of concern through effective sharing of information of professionals and foster parents;

- If the responsibility for the disruption is considered to lay with the foster parent and their response to the child, a structured plan of work to improve responses to the child will be formulated along with an appropriate training programme. In these circumstances the issues of concern may lead to a foster parent review.

Ending Placements

Every placement should end in a planned and considered manner. Even if the placement has not gone well, the foster parents and the child or young person will feel better if the move is carried out calmly, giving everyone time to express their feelings. Most placements do end happily, with the child or young person returning home, or in some cases moving on to a new permanent family. However the placement finishes, foster parents will experience all sorts of mixed emotions and social workers need to allow time for foster parents to talk about how they feel.

Ideally, a LAAC review should take place before a placement ends in an unplanned way i.e. not as part of the care plan. The exceptions would be:

- Where the foster parent/s decide they are no longer able to continue with the placement and there is no time to organise a case review.

- Where a parent of a section 25 accommodated child wishes the child to be returned to their care and there is no time to organise a review.

- Where the child’s social worker considers that there is an immediate risk of significant harm to the child or others.

When any placement is ending, foster parents and Fosterplus should work with the child’s social worker and others to help the child to understand why they are moving, and we should support the child through their transition to a new living situation, whatever that may be.

Even in situations where moves were not planned, our aim is that Fosterplus and foster parents will work together to ensure sufficient time for planning and arranging the next placement. Where foster parents wish to end the placement, we expect a reasonable notice period. We will never move a child on the same day, other than in very dangerous circumstances, where serious harm will occur if the child is not moved.

Unplanned Ending Meetings

If the placement of a child or young person with foster parents breaks down, the responsible local authority will usually want to hold an unplanned ending meeting. However if the local authority do not hold an unplanned ending meeting within a reasonable time scale, Fosterplus will convene one inviting the local authority to take part.

Placement Disruption or Unplanned Ending Policy

Fosterplus Placement Disruption or Unplanned Ending Policy can be accessed on CHARMS/Download

The unplanned meeting should involve all those closely involved with the child and the family, including the child’s social worker and supervisor, the permanent foster parents, the supervising social worker, and any other relevant parties.

The objective of the unplanned ending meeting is to examine the various elements of a match or placement and the reason for the disruption in order to ensure that:

- The children’s current and future needs can be met;

- The foster parents can be helped to recover from the experience;

- Practice can be improved.

Unplanned ending meeting –

The meeting will be recorded and foster parents should receive a copy of the minutes.